Predicting the demise of 60/40 has been a fool’s errand.

To be sure, it’s not hard to parrot a plausible narrative for why a traditional, balanced portfolio will struggle to deliver the “have your cake and eat it too” kind of performance witnessed over the past two decades (give or take).

For one thing, life doesn’t offer up many “have your cake and eat it too” opportunities. They aren’t supposed to exist. Generally speaking, purported instances of such opportunities usually fall into the “if sounds too good to be true, it probably is” category. In addition, bond yields theoretically can’t go much lower.

This is a bit of tired topic, but it’s timely. The universe of negative-yielding debt is back at record highs, which ostensibly argues against the notion that fixed income can buffer prospective losses in equities.

With governments issuing massive amounts of debt to fund stimulus and central banks coming out overtly in favor of policies that countenance inflation overshoots to make up for past misses, it’s not terribly difficult to posit a situation where bonds have a hard time rallying much further, even if the macro backdrop retains its disinflationary character.

In addition to the ostensibly limited scope for bonds to rally, the market’s sensitivity to monetary policy communications prima facie raises the odds of “tantrum”-like events in fixed income. That could mean that bond allocations become a source of considerable risk.

Read more:

Bridgewater ‘Tweaks’ Risk Parity Model, Moves Into Gold As Bonds Get More Risky

Are 60/40 And Risk Parity Funds Doomed? (And The Two Weeks Gold Bulls Like To Forget)

That, in a nutshell, is the argument, and to the extent it’s accurate, the reliably negative correlation that underpins risk parity and balance portfolios more generally, could break down, leading to the dreaded “diversification desperation” during periods of equity weakness.

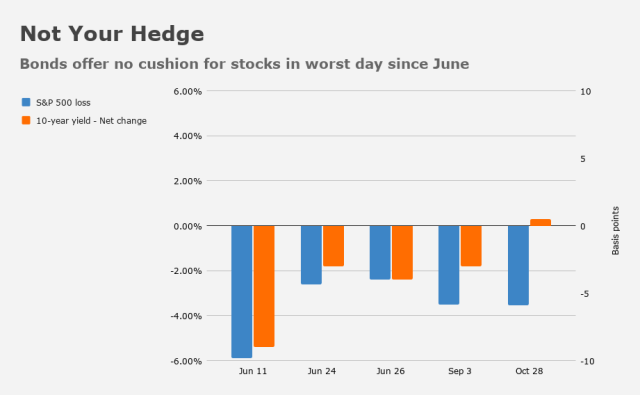

2020 has seen several instances of simultaneous selloffs in stocks and bonds, particularly in March, when the Treasury market briefly “snapped,” but also late last month. For example, on October 28, US equities plunged nearly 4% and bonds were useless as a hedge (figure below).

What that visual also shows, however, is that since March, sessions characterized by outsized weakness in equities have, in fact, been accompanied by lower yields, meaning bonds were a cushion.

But even during March, a 60/40 portfolio outperformed the S&P. The chart (below) uses a (too) simple methodology for constructing a 60/40 strategy, but it does the trick as far as offering up a handy visualization.

You’d barely be trailing the S&P this year if you held this simple version of a balanced portfolio, which includes only large-cap US stocks, Treasurys, agencies, and investment grade corporate bonds.

As the visual shows, you’d have fared much better during the height of the panic, despite several days of acute conditions in the Treasury market.

Read more:

Invariably, 60/40 critics will remain… well, critical. For example, Goldman said Friday that the biggest pushback they received from those who believe their 2021 outlook for US stocks is too bullish, revolved around the notion that inflation might take off, pushing bond yields sharply higher.

I have my doubts. The lingering effects of the pandemic (e.g., structural damage to the labor market) as well as the developed world’s misplaced affinity for austerity, could easily depress aggregate demand, weighing on yields and inflation. At the same time, central banks have made it clear they intend to keep bond yields low.

Evidence to support the idea of replacing the bond portion of a balanced portfolio with something like gold is mixed, at best. At one point in March, gold plunged as the dollar surged with US real yields, for instance. In addition, gold’s correlation with rising stock prices over the summer suggested the yellow metal was trading more as a debasement hedge than as a safe haven.

As far as replacing bonds with something like private debt (an idea I’ve heard bandied about lately) is ludicrous, at least for most investors. Do you really think bundles of loans originated in the exciting world of direct lending, for example, are a replacement for Treasurys or agency MBS?

And, you know, people are starting to say some things (and pose some questions) while debating this issue that seem patently absurd. I haven’t listened to the whole podcast, so it’s unfair for me to cherrypick, but consider the following set of questions posted by Bloomberg in the teaser article for a conversation with Peter van Dooijeweert, managing director of multi-asset solutions at a subsidiary of Man Group:

- Do you go 100% risk-on?

- And then what?

- How do you deal with a crash?

- What does it look like with 100% risk on?

- What are the tails?

- What are the crashes like?

I can answer all of those questions. In order:

- No.

- You expose clients to catastrophic losses.

- By traveling to the bottom of a Laphroaig bottle and staying there.

- It looks dangerous.

- They are fat.

- Existential.

You can direct further questions to my PR department.

My son has a great sense of humor relative to the absurdity of human beliefs. So he sends me podcasts occasionally depicting these. Thanks for an additional one…

That April 5th note is scary on re-read. Unbelievable year.

That asset class is if kind of over. So, too, might be conventional thinking that was applied from 1985 to 2020.

Let’s all hope we get another rally. (Easy to see how it could happen.) Buy ourselves six more months of time to try to sort it out. It’ll be a great opportunity for small players, i.e., retail, to sell ahead of the big boys. haha

No way RIAs and others are going to sit on dead money. But, what?

I suspect high net worth clients have already been receiving research from Goldman, BoA, JPM, and DB, on what to do with the dead money 40. I’ll be curious to read what drips into the public domain from these teams.

We’ve been using SPX deep OTM Puts for the last 3 years.

But we’re actually questioning the rationale. If you have a long enough horizon, what is the purpose of trading off perf. for vol. reduction? Sure, institutional clients love vol. reduction coz career risks. But what if profit maximization is your goal?

As a practitioner this article addresses an issue that is top of mind for me. In case anyone cares here is my observation. I typically like to invest in spread product for my fixed income allocation. I have become a lot pickier about spread product lately. With these rates it really has little purpose. I do still use some closed end funds where i can invest for clients and still get a decent risk adjusted yield if they trade at a high enough discount. Otherwise not a big fan. If fixed income is a poor hedge (spread product), is not very liquid (spread product) , and offers little yield (spread product), what is the point? So now I am down to agency, treasury and maybe but not likely very high grade taxable muni debt for the fixed income allocation. If I am worried about duration, including my equity allocation- the answer seems to be to look away from tech, growth etc. Why? I want to use my duration bucket for my bond allocation- that is with the yield curve pretty steep from 10-30 years a long US Treasury provides comparative high sovereign yield and is a decent hedge to equities. What can hedge that duration. Shorter duration equities- that is value, international which has a decent value tilt, and small and mid-cap equities which have lagged. So now I am going to tilt away from equity growth and spread bond product. I wil be emphasizing equities which do better in a bit of a bounce back coming out of the recession with a long US Treasury/Agency hedge. Best I can do- and I will probably throw in some gold and real estate stocks to lower the equity correlations….I probably shoot for a bit higher equity allocation as well- so maybe the new 60/40 is now 65/35 or 70/30…..

WW, your responses to the podcast questions caused me to LOL!!..Sadly because it’s true…