Do you believe we’ve “crossed the Rubicon” where that means policymakers are increasingly inclined to view the world through the lens of Modern Monetary Theory even if they insist they’re doing no such thing?

If the answer is “yes,” you’ll be forgiven. The superfluous middleman notwithstanding, central banks are engaged in debt monetization.

That’s been true for a long time, of course. What’s new is that the “match” between government borrowing and central bank bond-buying became so glaring following the pandemic that the charade was difficult to obscure, even in countries where the public isn’t exactly famous for its capacity to grasp nuance (e.g., the US).

The figure (below) is about as straightforward as it can be.

If you ask SocGen’s Albert Edwards, “this is not just a short-term response to the pandemic.”

Rather, “this super-expansionary policy nexus is here to stay until policymakers are forced to reverse course,” he wrote, in a Thursday note.

This brave new world of monetary-fiscal partnerships is part and parcel of Edwards’s “Great Melt” thesis, which, eventually, will supplant his long-held “Ice Age” framework. But not just yet.

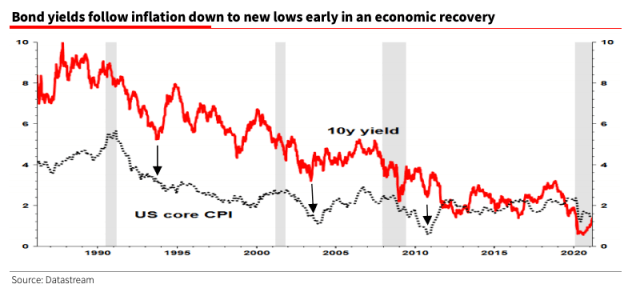

In fact, Edwards agrees with Guggenheim’s Scott Minerd, who this week suggested 10-year US yields could still go negative, the recent bond selloff and ostensibly inflationary policy dynamics notwithstanding.

“No doubt, prices will rebound from post pandemic lows but given the surplus capacity throughout most of the economy and high levels of unemployment, any increase in the rate of inflation is likely transient,” Minerd wrote, adding that,

Against [a] backdrop of rather benign inflation and easy money, investors will be tempted to reach for yield. An upward sloping yield curve is one of the few avenues remaining that provides an opportunity for fixed income investors to boost current cash flow. At the end of the day, taking on duration risk to get any reasonable return on cash will prove a temptation too great to resist.

I actually don’t disagree with that, and neither does Edwards.

“The extreme fiscal stimulus sets the markets up for a burst of strong growth that has already been more than fully discounted by investors, raising the risk of a cliff-edge towards the end of the year,” he said Thursday, mentioning David Rosenberg in the process. “This is likely to combine with a slump in core CPI, which always falls sharply immediately after a recession ends, as productivity soars and unit labour costs collapse.”

The figure (above, from Albert) shows yields rising at the end of recessions only to fall again.

“Those betting on a quick return in inflation may be sorely disappointed,” Edwards remarked, adding that “Minerd’s forecast of negative 10-year bond yields looks good to me.” (As an aside, one wonders how Minerd’s pseudo-forecast of Bitcoin $400,000 looks to Albert.)

But coming full circle, it would be a mistake to say Edwards doesn’t think inflation is coming eventually due (mostly) to the Fed’s tweaked approach to its mandate. Average inflation targeting and the decision to effectively jettison what many view as outdated notions of “full employment” means “we’re driving flat out with the foot pressed hard on the monetary gas pedal with the wind blowing through our hair,” as Albert put it.

The problem, he cautioned, is that “by going all in on that bet now, investors have likely gone too big, too soon, and are very exposed to a downside shock.”

I love how people who think that dozens of Congresses will pass the necessary combination of prudent tax increases and spending cuts necessary to have Federal surplusses large enough to pay off $20+ trillion worth of debt look at MMT advocates as the kooks.

That is a hilarious comment! Spot on too.

I’m with Albert. Zooming out, the trillion dollar question is what will it take to break a powerful 40 year trend of demographics, debt, technology and globalization? Certainly something of much greater magnitude than we’ve seen so far.