One of the reasons I gently (and ironically) discourage people from consuming too much in the way of “alternative” commentary around markets and geopolitics is that the vast majority of it is pure counternarrative — that is, counternarrative for its own sake.

Or, actually, not for its own sake. Rather, for the sake of generating web traffic by preying on the gullible.

Prior to big-tech’s efforts to demonetize and otherwise knee-cap platforms associated with foreign influence campaigns and propaganda, counternarrative was a lucrative online business. “Anti-establishment” content is popular in the western world thanks in no small part to the worsening plight of the middle class, and their search for scapegoats.

The highly-educated (e.g., people with post-graduate degrees) aren’t generally amenable to counternarrative for its own sake because they typically ask “the next question.” Almost as a rule, no purveyor of counternarrative for its own sake will ever answer (or even acknowledge) “the next question.”

I’ll give you a familiar example.

Many Americans are suckers for the simplistic “Whataboutism” employed by the Russian Foreign Ministry and master spinstress Maria Zakharova (seen here with, unfortunately, Jen Psaki).

Zakharova routinely cites “examples” of what appear, to the average person, as instances of the western powers engaged in malign activities similar to those Vladimir Putin’s Russia engages in on a daily basis. In many cases, her “examples” are false equivalences, but even if they weren’t, Whataboutism suffers from a fatal logical flaw. If I do something wrong, I can’t exonerate myself by citing an instance of someone else doing the same thing. To attempt that is to admit that what I did was wrong.

No one would fall for that in an everyday context, but Americans are duped by it all the time when it comes to international relations and geopolitics.

The most recent example was Alexander Lukashenko’s sky piracy. In defense of the indefensible, Russia (and many of the Kremlin’s arm’s-length, US-based surrogate portals, some of which masquerade as finance- and economics-focused websites), cited ostensible examples of the western powers doing something similar in the past. You probably read some of those accounts.

Let’s give Russia the benefit of the doubt and assume those examples aren’t false equivalences (they are, but we’ll pretend). The logic still dead-ends rather quickly: “So, you’re saying the episodes are similar?” “Exactly.” “Were the other episodes bad?” “Yes, definitely.” “And, just to be clear, you’re comparing those episodes to what happened in Belarus?” “Yes.” “Then how is Lukashenko’s behavior not bad too?” Dead end.

That’s “the next question.” Notably, it’s not a death knell for those writing serious counternarrative. Legitimate investigative journalists, for example, often engage in de facto counternarrative, even if they wouldn’t characterize it as such. (There’s an official narrative, an investigative journalist gets a tip suggesting the public isn’t getting the whole story and then investigates not just “the next question,” but all questions.)

Counternarrative for its own sake isn’t actually interested in the truth at all. Regular readers are familiar with my stolen TV hypothetical. If I steal your TV while you’re at the grocery store and then I get caught, I’d be laughed out of the courtroom if, in an attempt to defend myself, I stood up and rattled off a list of all episodes of TVs being stolen in the last year. (“As you can see, people steal TVs all the time. As such, I’m free to go. Thank you very much.”)

The same reluctance to engage with, let alone answer, “the next question” is a mainstay of what’s often described as “alternative” financial content. Note that I’m not referring to any analysts here or to anyone employed professionally in capital markets. I’m solely referencing portals and personalities who traffic in cheap, economic counternarrative for profit.

That’s a difficult distinction to draw, though, because often, those portals and personalities cite research produced by professional analysts and economists to support their narrative. In many cases, the implication is that they’re somehow connected to, or otherwise acquainted with, economists, analysts and the professionals they cite. In almost all cases, they’re not acquainted. I can tell you that with 100% certainty.

This is important, because what it means is that other people get roped into, and associated with, mass produced counternarrative without their consent.

Banks are, in many respects, obliged to stick to some version of orthodoxy when it comes to economic research and market commentary. You can’t simply “go rogue” one day and pen something totally at odds with prevailing, accepted economic theory without running afoul of somebody internally. You may even run afoul of compliance, depending on just how “rogue” you’ve gone.

Those strictures don’t rule out provocative research, but they do generally prevent envelope-pushing, which leaves the door open for purveyors of counternarrative to do the envelope-pushing themselves by, for example, cherry-picking downside scenarios from a given bank’s S&P forecasts to create misleading titles like: “XYZ Says US Stocks Could Fall 21% By September.” (And just like that, XYZ bank is “bearish” as far as everyday investors know, even if the original research was overtly bullish.)

Let me show you how this works, in practice, and also how, true to Zakharova’s template, the process dead ends when “the next question” is asked, sometimes to the detriment of public discourse around important topics.

In a sweeping, 49-page note dated June 21, Deutsche Bank explored what they called “The return of big government spending.” It’s a good piece. It’s comprehensive, well-written, informative and, generally speaking, orthodox. In other words, it’s exactly what you’d expect from a 49-page note written by a senior economist at a major bank.

At the current juncture, market participants are obsessed with government spending, the fiscal-monetary nexus (i.e., the monetization of government debt by central banks) and the possible perils of such circular funding arrangements. As such, it would be easy to create a highly compelling (i.e., click-generating) piece of content simply by excerpting a tiny fraction from four-dozen pages of in-depth analysis.

For example, Deutsche Bank notes that,

Today, record high public debt has only remained manageable because of the structural decline in interest rates as well as an inauspicious alliance between monetary and fiscal policies, where central banks have de facto (not de jure) monetized rising chunks of public debt. As major central banks like the Fed, the ECB, BoJ and BoE are effectively operating at the limits of monetary policy by pursuing ultra expansionary monetary policies for many years now (thus unavoidably creating considerable risks to medium/longterm price stability), most governments find themselves still able to finance their large budget deficits and maturing debt at historically low (or even negative) yields. Although these monetary policies are stabilizing public finances and the economies in the short term, they reduce the incentives for sovereigns to shift towards fiscal consolidation in the medium term and therefore imply significant medium to long-term risks.

Sounds scary. And who knows, maybe it is! Contrary to popular belief, I’m by no means wedded to the idea that there are no risks from overt fiscal-monetary cooperation. Rather, my contention is (and has always been) that it’s nothing new — that the post-pandemic world is no different than the 2008-2019 world when it comes to circular government funding.

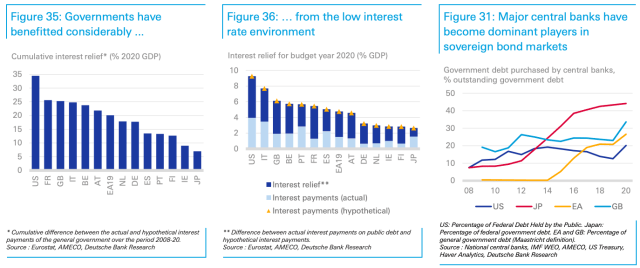

Deutsche Bank does some interesting math. Specifically, they try to “quantify the benefits from falling interest rates by calculating the interest payments that would have materialized if implied interest rates on government debt had stayed constant during the period 2008-20 at their 2007 levels (hypothetical interest payments).” They call the difference between those rates and actual rates “interest rate relief.”

As it turns out, that “relief” has been substantial. “We reckon that the cumulative interest relief for the period 2008-20 amounts to around 35% of GDP for the US, roughly 25% of GDP for France, the UK and Italy and somewhat below 20% of GDP for the Netherlands and Germany,” the bank said (figures, below, from Deutsche Bank).

The implication (obviously) is that central banks have played a key role (alongside the structural decline in interest rates) in keeping public debt ratios for advanced economies lower than they would otherwise be.

You don’t need any experience operating a website dedicated to dour narratives about debt, deficits and fiat currencies to understand how easy it would be to generate 50,000 clicks based on those short excerpts. For example, you could use this title: “Uncle Sam Gets $7.5 Trillion Gift From Central Banks.”

But “the next question” is very inconvenient for deficit hawks, debt doomsayers and QE critics.

Interest rates are a policy variable — by definition when it comes to administered rates, certainly at the short-end and also across the curve when a developed market monetary authority decides to implement yield-curve control. Central banks are, like treasury departments, just another organ of the debt-issuing sovereign. The debt-issuing sovereign also has a monopoly on the issuance of the currency in which the debt is denominated and in which interest is paid.

In fact, then, none of the language we use to talk about any of this makes much sense. Notwithstanding the bank intermediary in the QE equation, the bottom line is this: The sovereign, which sets interest rates, is creating currency to buy interest-bearing versions of its own currency from itself, then paying itself interest in that same currency.

It’s so self-referential — so self-evidently circular — that it virtually screams to be abandoned in favor of simply creating currency and spending it. The italicized “bottom line” (from the preceding paragraph) is nothing if not evidence that we’ve become slaves to our own imaginary constructs.

When you conceptualize of this situation using the standard vernacular, you come away thinking we’re teetering on the edge of total collapse because the entire developed world is running a massive, multi-trillion-dollar (-euro, -yen, -loonie, -Aussie) Ponzi scheme that’s inherently doomed. We’re on “borrowed time.” The “debt clock” is ticking. We’ll have to “pay the piper.” And so on.

But the day of reckoning never seems to dawn. It’s been a dozen years. If it holds up for another dozen years, it’ll have outlived the careers of many an investor, trader and analyst. Hell, if you were over 45 for Lehman, it’s already outlived your career! (A reader once accused me of “recency bias” when I made a similar point. I don’t know about that particular reader, but I can’t remember much from birth through about 10 years old. Considering an optimistic assumption is that I live to be ~80, 12 years is a long-ass time in the context of a human lifespan minus the decade most of us don’t remember very well.)

What we’ve shown ourselves over the last dozen years is that developed countries can simply create money and spend it. The debt charade is just that — a charade. From a market function perspective, and also from the perspective of recycled global savings, the world does “need” US Treasurys. But the government has no actual need to issue them in order to spend. The same is true of gilts, JGBs and AGBs.

That’s the real takeaway from the excerpted passages from the Deutsche Bank piece. Of course, the bank doesn’t say that. Or actually, they almost do, but the section entitled “The budget constraint revisited: A country’s currency status and central banks as guarantors of fiscal stability,” is followed by a section called “The dark side of high and rising debt.” (Cue the Hollywood thunder noise machine.)

You can’t blame Deutsche (or any other bank) for not throwing caution completely to the wind on the way to posing the pseudo-existential questions that need to be asked right now. But you could blame independent observers, commentators and portals ostensibly dedicated to sparking debate if they don’t ask “the next question.”

And that’s really the irony when it comes to so-called “alternative” finance portals — they’re almost all dedicated to some version of budget orthodoxy and conventional wisdom when it comes to fiscal policy and debt dynamics. There’s nothing “alternative” about them.

Deutsche writes that “In a very simplified way, a country’s public debt path can be viewed as unsustainable if the fiscal policy stance leads to a permanent rise of the public-debt-to-GDP ratio under plausible macro assumptions.”

And yet, again, we have to ask the existential question — “the next question,” as it were. What is “debt” when it’s denominated in the issuing-sovereign’s own currency? Not “debt” in any real sense of the word. Indeed, there’s a strong argument to be made that, when properly conceptualized, no advanced economy has any “debt.”

Invariably, portals and personalities dedicated to debt and deficit doomsaying resort to familiar tactics to refute that idea. “Ask Greece about that,” they’ll sneer. Or they’ll point to Argentina.

But, true to the Zakharova playbook, those are false equivalences. Greece isn’t a currency-issuing sovereign. And Deutsche’s research alludes to the fact that, increasingly, people are beginning to wonder whether advanced economies are constrained at all. For example, the bank writes that,

Most economists agree that emerging markets suffering from “original sin” (inability to issue local currency debt in international markets) or “debt intolerance” (linked to a country’s default/inflation history) have to meet the budget constraint as they can be pushed into sovereign default because of a substantial amount of foreign-currency debt and the economy’s restricted potential to generate hard currency through exports. Still, there is a controversial debate on whether or not this budget constraint is similarly binding for major advanced economies that are mainly (or exclusively) relying on domestic currency debt.

What if there is no such constraint? Or what if the threshold beyond which it is binding for advanced economies is so far from where we are today, that the developed world could have financed everything from a green revolution to Mars colonization by now without any kind of fiscal headaches at all, let alone any debt “apocalypse.”

Those are the “next questions” we should be asking. This is the real counternarrative. And it’s delivered here not for its own sake, but for the sake of society.

Trump being the master of the counternarrative and false equivalency.

I’ll borrow from Alan Watts here on Money, “Imagine you are a carpenter and you show up on the job site and the boss says ‘sorry, we’re out of business, we’re all out of inches.” So you say “what do you mean? we have lumber and workers and land and people need the house right?” “Yeah but you see we just do not have anymore inches, it’s impossible.”

We’re still addicted to the idea Money exists in and of itself. MMT is really just acknowledging that money is a bookkeeping tool and nothing more. You don’t build a house with money. You don’t feed an army with money. Inflation and Deflation are just examples of what happens when you’re doing the bookkeeping poorly.

In an episode of Rick and Morty, Rick destroys the intergalactic federation by changing a cell in a spreadsheet from 1=1 to 1=0 making the entire intergalactic economy collapse immediately as the “Dollar” became worth zero dollars. This sounds like cartoon nonsense but it’s basically where we are. Until we start modeling the economy in terms of physical properties instead of dollars and driving the economy through policy instead of interest rates and QE we’re going to continue trying to grow crops, etc. by putting more numbers into excel.

As I so often seem to comment, the constraint to debt monetization seems to be the rapidly expanding wealth gap and the crowding out of the middle and lower class from an ever increasing portion of American life. Healthcare, education, home ownership, (food and other commodities these days 😉 )

Your piece on the feds lack of self awareness in this regard (several months back if remember correctly) was a beauty.

The highly-educated (e.g., people with post-graduate degrees) aren’t generally amenable to counternarrative for its own sake because they typically ask “the next question.” Almost as a rule, no purveyor of counternarrative for its own sake will ever answer (or even acknowledge) “the next question.”

There are symptom solvers and problem solvers.

“There are [many] symptom solvers and [few actual] problem solvers.” This condition persists because we generally don’t know how to frame problems properly. All adaptive systems, those that react to changes in their internal and external environments, all have explicit or implied goals they must achieve or maintain to remain at a steady state within the limits of their resources. All problems are the same — not maintaining system performance within required limits. The reasons for failing to achieve adequate performance vary, but in business firms the reasons for failures in performance are virtually all the fault of bad management. Symptoms are neither causes nor problems. Rather they are legible signposts that show bad performance and suggest causes. Symptoms themselves cannot be “fixed” and the problem (bad performance) can only be solved by eliminating the causes. As suggested by fredm421, all constraints are resource-based.

Yep.

Our only restrictions are physical.

So what’s say the Fed decides to issue every single United States citizen 1 Million dollars? What would actually happen? A ton of spending, inflation, tax receipts, and the hottest economy that the world has ever seen. No more homelessness, hunger, poverty (for a time anyway).

Why not just do that then?

This is an interesting proposition. Lets say the Fed by some mechanic deposited $1,000,000 into every persons new free checking account at the USGOV bank which they just setup.

So first I imagine everyone wipes out all consumer, mortgage and student loan debt. A massive multi-Trillion dollar surge hits the banking industry followed by a complete drop in revenue. Private banks are set for 100 years and publicly traded ones pay the biggest dividends and bonuses in history then immediately begin to struggle to survive.

Next people start quitting jobs they hate and going to college, trade school, moving abroad, etc. Open job positions begin to climb rapidly driving up wages.

Next people begin to start spending on things they have always wanted to do. Home repairs and renovations, fancy cars, travel and having children. The next baby boom is beginning.

Interest rates start to normalize to balance the demand as inflations starts and investments are shifted to more stable less speculative instruments.

Then a couple years in people will likely start looking at those ROTH IRA’s with interest… I mean I can max out my contributions annually with ease. The stock market already flying high on enhanced demand for goods and services goes hypersonic.

So far so good.

But there will be some real big losers here. Imagine you owned the next 30 years of a students income at 6+% interest or you owned $35k in credit card debt on a bunch of US families. Instead of milking them for the next few decades… you just get your cash back. That sucks, better things stay the way they are… You can never let people out of debt bondage.

The fed wouldn’t issue the money. The fed would purchase the treasuries necessary to keep the long end of the curve from running away (though, hey, maybe they’d just let the long end run away).

Possible results include asset price inflation to make today’s seem tame (assuming the fed continues with controls) and real economy prices spiraling due to increased consumption without increasing supply (I suppose we could call them supply chain disruptions if they prove some semblance of fleeting)

Asset price inflation definitely (already been seeing that anyway). Why do you assume there wouldn’t be an increased supply? I mean initially we’d see what we’ve been seeing the past year vis a vis inflation and things selling out. But increased demand would drive increased production and more efficient production. With everyone spending all this money and having ample supply of it available, business revenues would fly through the roof while labor for crap jobs would plummet. You’d see an immediate uptick in automation purchases and hiring for automation innovation specialists. Skilled labor would become the only labor pool widely available and that pool would expect to work on things that they believed in.

An interesting thought experiment to say the least.

the supply chain disruption joke was meant to imply the possibility of long term supply increases.

Glad we agree on the asset price side.

One of the most tragic commentaries on the US is how the kleptocrats and oligarchs (including Wall Street and both political parties) have gaslighted nearly everyone into simultaneously believing:

1. the US is the richest country in history

2. the US is speeding toward bankruptcy

This is a contradiction. Not only is it bald-faced absurd, but it is a purely-mental prison of our own design. However, I also think it may lead to one of the greatest ‘own goals’ in history. As long as the contradiction is forced upon the world via orthodoxy, and it is swallowed and believed, the world will react to it as if it is reality. Because reality is intersubjective. That means, to me, it’s far, far likelier that the currency (issued by the orthodox high priests) will devalue in a type of soft default, than that the wealthy and powerful will ever voluntarily restore the ‘solvency’ of the ‘national’ ‘debt’ by using their immensely-adequate wealth. The country is not insolvent in a real economic sense, and the debt is not debt – the problem is that the nation is not “a nation”, really. Don’t be fooled by the flag waving and jingoism of sociopaths, there is simply no collective enterprise. Call it what you like, or choose your favorite analogy: extractive imperial colonialism, neo-feudalism, or an LBO on an otherwise sustainable operation that siphons off everything and leaves a dead carcass.

Yup, colonialism worked so well abroad they brought it home. There is a reason Doctors without Borders operates in the US.

I think what you really just described is a virus.

That’s why politicians are the gangsters of today. Some will say that’s too harsh so maybe I should say they are the least able to perform the functions that modern society needs from the role of politician. Certainly there are modern pols who mean well, but they are dupes (or martyrs at best) in an organized syndicate dedicated to sucking up as much wealth and power as they can for themselves and their capitalist enablers. Even when they can get a majority to support something worthwhile, they lack the technical skills to get it done. They are experts at manipulating the psyche of the masses to the point of getting us to sacrifice our sons and daughters in the fight against whatever bogeyman they can conjure to keep us imprisoned by our own fear.

I apologize for the rant, it’s born of frustration.