The Bank of England hiked rates for the 12th straight meeting on Thursday, in what may or may not be the final hike of the cycle.

The new statement explicitly referenced wage-setting and services sector inflation in a tacit admission that price pressures are embedded across the economy and may prove difficult to dislodge.

The vote was 7-2. The dissents were (obviously) Swati Dhingra and Silvana Tenreyro. Rates are now the highest since October of 2008, weeks after Lehman collapsed.

The bank said that assuming no additional turmoil in the US, “there is likely to be only a small impact on GDP from the tightening of credit conditions related to recent global banking sector developments.”

The decision came with new projections. As a reminder, inflation in the UK has been running double-digits consistently for nearly a year. The new forecasts still show a quick decline to target (by year-end 2024), but the drop is now expected to be a bit less rapid compared to February’s outlook.

“Food price inflation is likely to fall back more slowly than previously expected,” the bank said. The YoY pace of food and non-alcoholic drink price inflation exceeded 19% in March, the highest in 45 years.

I doubt there’s much utility in lampooning the MPC’s forecasting shortfalls any further. This long ago moved beyond the realm of the absurd into some desolate netherworld where economic hubris is condemned to an eternity of frustration and suffering.

The sharp drop in forecasted inflation is due in part to base effects. Despite an overtly cautious tone, the BoE did say that “nominal private sector wage growth and services CPI inflation have been close to expectations,” even as they’re still elevated.

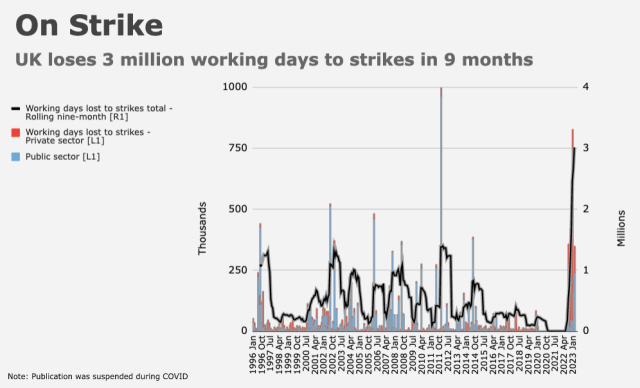

The disparity between private and public sector pay in the UK has precipitated strikes and generalized social unrest.

According to ONS, some three million work days were lost to labor actions since the statistics office began gathering the data again last year following the suspension of collection during the pandemic.

You wouldn’t know if from the forecast, but the BoE does view the risks around inflation as “skewed significantly to the upside, reflecting the possibility that the second-round effects of external cost shocks on inflation in wages and domestic prices may take longer to unwind than they did to emerge,” to quote the new statement again.

The labor market is likely to remain tight, and the economy has been “less weak than expected,” the BoE went on, noting that GDP may actually grow if you “exclud[e] the estimated impact of strikes.”

The forward guidance was for a conditional pause. “If there were to be evidence of more persistent pressures, then further tightening in monetary policy would be required,” the bank said.

In the summary of the new projections, the BoE helpfully noted that declining inflation “doesn’t mean that prices will fall,” only that they’ll “stop increasing so quickly.”