The increasingly tense standoff between the bond market and the Fed will culminate this week in the March FOMC.

There are a number of dynamics playing out simultaneously. Some of them are generic, some are far more nuanced.

Most obviously, bond volatility picked back up headed into the weekend, a somewhat disconcerting development. Many assumed the rates tantrum was poised to abate after last week’s supply went down without the kind of violent indigestion that characterized February’s seven-year auction. The long-end led Friday’s losses, with the 20-year underperforming ahead of Tuesday’s sale.

The generic narrative revolves around stimulus, an aggressive vaccination timeline in the US, and a prospective infrastructure bill, which together are assumed to presage robust growth outcomes, broad reopening across the services sector by summer, higher deficits, and more borrowing. So, we get higher yields, a pro-cyclical bent in equities and (sometimes shrill) inflation warnings.

Some of that is desirable for the Fed, but the concern (as it relates to the reflationary zeitgeist) is a disorderly backup at the long-end, which can tighten financial conditions and push up borrowing costs. There’s quite a bit of duration risk embedded across assets and portfolios, so an unruly bear steepener would be a decidedly unwelcome development no matter what it’s purportedly “saying” about the macro outlook.

Crucially, it might not be “saying” anything at all. Rather, it might be an expression of indeterminacy. “Violent bear steepeners reflect anxiety due to the rapid rise of uncertainty about policy over an unspecified horizon,” Deutsche Bank’s Aleksandar Kocic said Friday, adding that,

Unlike actual cycles, which are based on conviction, bear steepeners reflect absence of conviction. They are not a gradual adjustment to any imminent action, but resetting to higher anxiety levels and remaining there until they are either realized or disputed. Bear steepeners can be seen as an invitation to a dialogue with policy makers, their intensity and volatility intended to attract attention.

In a March 10 note, TD’s rates team cited a “high bar for the Fed to hike” and the elevated level of duration supply in arguing that the 5s30s steepener has further to run.

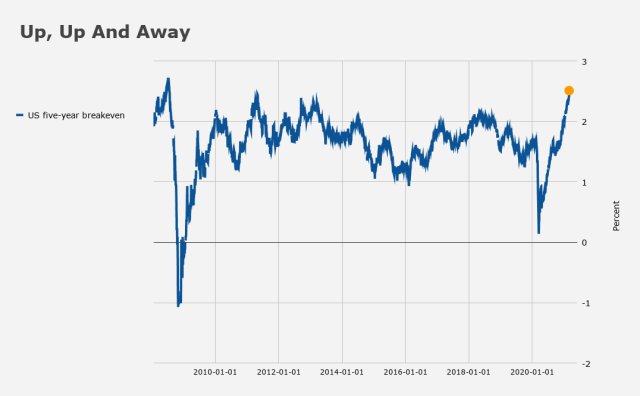

That trade is the subject of some debate. Last month’s dramatics around the disastrous seven-year sale stick out on a chart (the orange dot in the figure, below, shows the curve at the steepest since 2014, while the red dot shows the volatility around the seven-year auction debacle and concurrent repricing of Fed expectations).

Five-year yields “have become unmoored in recent weeks, surging amid speculation that the [Fed] will need to start a cycle of rate hikes perhaps a full year earlier than officials have indicated,” Bloomberg wrote over the weekend, capturing the debate and noting that shifting expectations have “roiled the outlook” for the 5s30s, “a classic iteration of the reflation wager… even as the narrative of a stimulus-fueled recovery has only gained momentum.”

For TD, the Fed’s tweaked mandate means it’ll be hard for the short-end and intermediates to become too unanchored. “The Fed is looking for an inclusive labor market recovery and inflation to overshoot the 2% target to hike rates,” the bank wrote, in the same March 10 note. “This should help anchor the five-year sector.”

For their part, Deutsche Bank’s Jiefu Luo and Jose Gonzalez flagged the five-year point as “excessively cheap” on a PCA model. They cited the same fateful day in late February. “This is not entirely unexpected, given that the five-year point experienced a dramatic move on the curve over the last two weeks [including] a six-sigma selloff event” on February 25.

They went on to compare this iteration of a rates tantrum to the most famous episode in 2013. “[The] similarity between today’s and 2013 markets suggests that the recent underperformance of the belly could be a near-term regime shift,” Luo and Gonzalez said, suggesting that the belly “has reset to a new higher level corresponding to the new regime” and noting that post-taper-tantrum, the five-year “moved to a higher level and remained within a tight range for more than two years.”

But there are differences between then and now. Positioning prior to the 2013 tantrum was record-long, Deutsche wrote, in the same note. That amplified the selloff. Contrast that with today, when “real money and quant/CTA funds are already significantly short.”

One simple way to encapsulate all of this is just to suggest, as Bloomberg did in the linked article (above), that “the bet on a steeper curve isn’t kaput… it’s just due for a re-think” which could entail “ditching the wager if it’s grounded on the five-year note, which reflects a medium-term view of the Fed’s path, in favor of one based on the two-year, which still remains anchored in the market’s eyes.”

But it’s not just the five-year. In general, the market increasingly buys the narrative that realized inflation will pick up faster than the Fed thinks, leaving them behind the curve.

Of course, the whole point of average inflation targeting is to deliberately get behind the curve and allow inflation (and the economy) to “run hot.” The concern, for some anyway, is that policymakers will prove insufficiently adept at containing realized inflation if it manages to catch up to expectations.

In addition to addressing (implicitly and explicitly) the market’s expectations for the rate path, the Fed is also under pressure to at least reiterate that long-end yields rise at their pleasure and that any selloff there can be capped immediately (and with extreme prejudice) if necessary. The press conference should serve as a kind of mulligan for Jerome Powell, whose perfunctory remarks during a March 4 Wall Street Journal event were deemed insufficiently attentive by traders.

Consensus certainly isn’t looking for any kind of grand unveil of WAM extension this week. And nobody expects anything like overt nods at outright yield-curve control. But that’s not the point. What the market wants (and, arguably, needs) is just some kind of reasonably convincing rhetoric that suggests the Fed is aware of the potential for rates volatility to cause problems quickly, and is prepared to address any such theatrics. Note that communicating preparedness means more than just alluding to the Fed’s “tools” and making nebulous promises to “use them,” as Powell is fond of doing. That talking point is (very) stale. At the least, the language needs to be revised so that when Powell reads from his bullet points, that one is a semblance of fresh.

In addition to all of this, somebody, somewhere, needs to address the SLR issue. Either relief will be extended or it won’t, but ignoring this noisy rattlesnake coiled in the back corner of the room isn’t going to make it go away. In fact, markets are becoming obsessed with it, and headlines trumpeting a record decline in dealer Treasury holdings risk making the issue a pseudo-mainstream talking point. Clearly, there’s political wrangling going on behind the scenes, but the clock is ticking, and folks want some answers.

As far as the 30,000-foot view, BMO’s Ian Lyngen and Ben Jeffery said Friday that the Fed “appears content to see a controlled rise in rates slowly remove any perceived froth in asset valuations [and] in the absence of any tone shift from Powell, the grind higher in yields will persists until something breaks.”

Were it not for the pandemic (which will probably mean Powell ends up lionized by the history books barring some kind of meltdown prior to the end of his tenure), Powell would have likely been remembered as the Fed Chair who did, in fact, tighten until “something broke.”

While overlapping causality with a concurrent escalation in Donald Trump’s trade war with China makes it difficult to pin all of the blame for the Q4 2018 mini-bear market in equities on Powell’s infamous “long way from neutral” misstep, there’s little doubt that he overestimated the market’s capacity to absorb rate rise. Yes, he changed course in early 2019, but he was under extreme pressure from the White House.

Additionally, those of you “old” enough to remember the moment Powell’s policy U-turn took shape (January 4, 2019) will recall that Janet Yellen and Ben Bernanke were quite literally sitting with him and staring at him as he took the exit ramp off the highway to “tighter,” made a left at the stop sign, crossed the overpass, then promptly made another left, before merging back onto the highway, this time going in the opposite direction towards “looser.” The figure (below) is a visual trip down memory lane.

Powell seems perilously close to repeating that song and dance. If he (tacitly) adopts an “until something breaks” approach again, he’ll get another unwelcome rise in real yields just like he did in 2018, and that will probably be accompanied by tremors across emerging markets and, eventually, a steep stock selloff stateside.

“Given our generally cheerful disposition, we cannot help but assume something will break sooner and with direr ramifications than the Chair would like to see,” BMO’s Lyngen and Jeffery went on to quip Friday.

By the way, how is the market going to react to news that the South African variant isn’t being thwarted very well by any of the vaccines?