“Apparently, investors have a great deal of confidence in the remedial powers of mass injections of monetary and fiscal stimulus”, Moody’s writes, in a new market outlook.

The tone is familiar. Nearly every piece of market commentary you care to peruse comes across as sarcastic – intentionally or not. Anyone disciplined enough to resist availing themselves of a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to employ unbridled bombast without risking one’s job, adopts an overtly dry cadence instead.

It’s not hard to understand why. Although some now claim there’s no “dichotomy”, the disparity between the data and the bounce in risk assets is glaring. The following visual is, in many ways, a heinous “chart crime”. To be clear, you shouldn’t take it seriously, other than as an amusing example of what happens when you endeavor to plot a furious bear market rally in equities with both soft and hard economic data in the middle of the worst downturn in a century.

What looks like a fat black line is actually a series of dots representing weekly jobless claims. The series is inverted. The points representing the last four weeks are so anomalous as to be wholly incomprehensible to anyone not apprised of the context. The Empire Fed gauge is similarly outlandish.

Posit a keen market observer, who, under normal circumstances, could “blindly” identify most widely followed economic indicators and benchmark indexes – that is, identify them by looking at a chart with no legend. Now imagine that person has been asleep for three months. Upon waking, our hypothetical Rip Van Winkle would likely know the blue line as the S&P, even if he would be surprised at the depth of the apparent selloff he missed while snoozing. The other two series (claims and the Empire Fed) would be almost impossible to identify, even with the benefit of the scales. In fact, having the scales would likely make the task even more difficult because nobody would believe you if you told them a total of 22 million Americans filed for unemployment benefits in the space of just four weeks.

That’s not to say the S&P should plunge to 1,000. The visual is in no way meant to suggest an “appropriate” level for equities. And, as noted, it is a chart crime of felonious proportions. But I don’t use it simply for the comedic value. Rather, what market participants should consider is that stimulus or no stimulus, Fed or no Fed, the kind of outright, total collapse witnessed in the past four weeks does not (cannot) happen without lasting ramifications. There will be scars from this, no matter how quickly the economy reopens. That’s where the ambiguity and the danger lies.

I would again point to the massive provisions banks have built for credit losses. I used this chart on Friday, and I’ll likely be using it again and again over the next few months.

It’s important not to lose track of the fact that the assumed realization of these losses necessarily entails credit events for companies and households. In other words: Real damage that will, at best, take time to heal and at worst, be irreparable.

There’s some (maybe even a lot) of truth to the notion that for many corporations (and even for many medium-sized firms and especially sturdy small businesses), this episode will be seen, in hindsight, as a “write-off” (to quote Jim Bullard) – a highly unfortunate turn of events, but one that in the final analysis, proved fleeting.

Others won’t be so lucky, though. Payments will be missed and households will suffer hits to their credit scores (does anyone really think the temporary suspension of delinquency reporting will do anything other than kick the can down the road?). The same goes for small businesses when it comes to fixed costs. That, in turn, curtails access to credit, which borrowers will need to get back on their feet. Are the same banks currently provisioning for tens of billions in losses going to turn right back around and lend to the same borrowers? The various Fed facilities and fiscal relief programs are designed to address these problems, but millions of people and thousands of businesses will fall through the proverbial cracks. They always do in recessions, and this one is particularly acute.

“A jump in government transfer payments to households helps to explain predictions of only a slight reduction for real disposable personal income [but that] may be overlooking something not seen on a broad scale since the Great Depression, which is the potentially widespread cutting of wages and salaries for the purpose of helping businesses cope with substantially lower sales”, Moody’s warns.

(Moody’s)

“Outright reductions in wage and salary income would [mean] a worrisome increase in deflation risks”, they go on to fret. “Not only would household credit risks rise, the credit standing of businesses would also suffer”.

As for corporate America, the Fed is backstopping credit markets, perhaps most critically for recently-downgraded issuers.

“The COVID-19 pandemic and oil price shocks have resulted in a marked increase in fallen angels to 23 as of April 13 from only two at the end of January”, S&P said Thursday, noting that globally, the number of fallen angels hit the highest since 2015. “The count of potential fallen angels (rated ‘BBB-‘ with negative outlooks or ratings on CreditWatch negative) has followed suit reaching 96”, the ratings agency went on to say.

And then there’s the bigger picture. The following is also from S&P, writing on April 14:

Potential bond downgrades (issuers rated ‘AAA’ to ‘B-‘ with negative rating outlooks or ratings on CreditWatch negative) rose sharply to a 10-year high of 860 on March 25, from 649 as of Feb. 28, on a combination of COVID-19 and a sharp decline in oil prices. The count of potential bond downgrades facing direct or indirect effects from the COVID-19 fallout is 277, roughly one-third of total potential downgrades. Social distancing measures to contain the spread of infections are weighing on tourism and travel, as well as demand for consumer discretionary products and eating out. This is reflected in the addition of 86 potential downgrades from media and entertainment.

Fallen angel risk may be understated by ratings agencies – or at least according to UBS, which estimates that $627 billion of the $2.6 trillion in outstanding BBB debt is “highly exposed” to mobility restrictions.

As you can see, that is a markedly more pessimistic assessment than ratings agencies have chosen to adopt.

Moody’s on Friday marveled at the sheer scope of the uncertainty inherent in the dispersion of professional forecasts for the US economy. “Consider the Blue-Chip consensus, or average, prediction of a 24.5% annualized sequential contraction by second-quarter 2020’s real GDP”, a note reads. “This average was bounded by an unheard of 24 percentage point gap between a -37% average for the 10 lowest forecasts and a -13% average for the 10 highest projections”.

One wonders why bother with forecasts when everyone is so clearly flying blind.

Of course, if you can’t predict the depth of the recession, then you’re not likely to have much luck projecting corporate profits either. Indeed, Moody’s goes on to exclaim that “the 10 lowest forecasts call for a 29% annual nosedive in core pretax profits, while the 10 highest projections have such profits declining by a much shallower 3%, on average”.

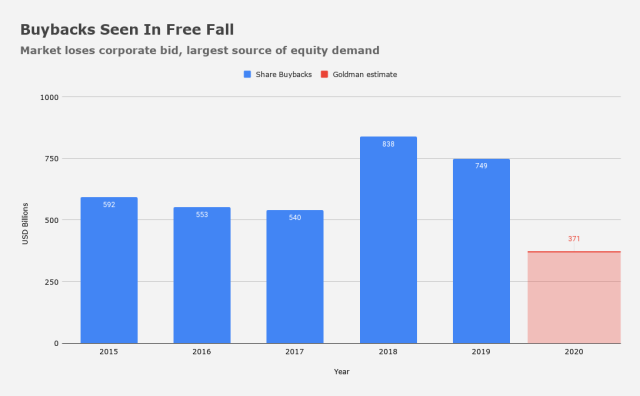

Somehow, in all of this, we’re supposed to price equities, which, in addition to losing what some old fashioned types still consider a key pillar of any good investment thesis (i.e., actual profits), will also have contend with a 50% drop in the largest source of real-life plunge protection – namely, buybacks.

“Since the beginning of March, 58 S&P 500 companies accounting for 29% of total 2019 buybacks have suspended their repurchase programs”, Goldman notes. “We believe mounting liquidity constraints and increasing political and social pressure will curtail buyback spending during 2020”.

So, where does all this leave us? Well, on a wing and a prayer, if you’re the type who’s skeptical about the bounce off the March lows.

“The dramatic rebound [in stocks] has left many investors scratching their heads due to the temporal mismatch between financial markets and the real economy, which has been in the full effect of late”, Axicorp’s Stephen Innes said Sunday. “But there are believers out there evincing the unprecedented actions by the Fed and Congress [while] a quick return to normalcy is little more than the removal of a single recessionary input – the virus”.

One item comes to mind that has not been mentioned.is….future income tax receipts by the IRS……Could be a subject for a future discussion but a definite negative factor when CFO’s start to calculate loss carry forwards. Not sure if anyone cares about deficits anymore after what we have seen lately !!!!

It stands to reason that with the shutdown lasting a month snd most Americans lacking even $1k of savings…. $1200 is not going to cut it even if everyone gets their jobs back in May…. which they won’t… without serious debt relief programs and direct payments to citizens this is going to cripple the consumption economy in perpetuity. I mean it wasn’t like we got wage growth even back when things were going great.

I hadn’t actually thought much about next year’s problem with receipts. For the working middle class, millions will undoubtedly have big gaps in this year’s income and many won’t get those expected January bonuses. Companies will find every way they can to shed taxable income through non-cash charges, crushing next year’s receipts, meager as they already are after the big tax cuts. What will they do with all that windfall. not give it to their workforce, that’s for sure. And remember, all these government payments are loans or non-revenue grants, all tax-free.