If the FOMC minutes hit on a day when no one is around to read them, do they make a sound?

Minutes from the Fed’s November policy meeting were released into a pre-Thanksgiving vacuum on Wednesday. So, besides being hopelessly stale, they were destined to fall on deaf ears and vacant chairs.

As a reminder, the November meeting (at which the taper was unveiled) came ahead of October’s jobs report. Subsequent data, including inflation figures and robust retail sales numbers, could be construed as an argument for a faster wind down of monthly bond-buying.

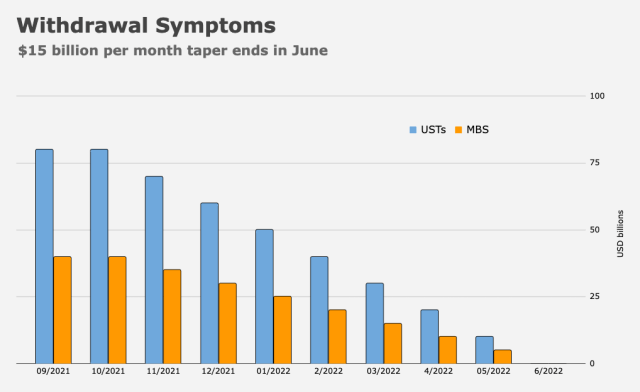

Last week, a trio of Fed officials including Clarida and Waller suggested the taper pace may need to be accelerated. Currently, it’s expected to be completed in June (figure below). Following Jerome Powell’s renomination this week, the market settled into bets on at least two hikes in 2022.

Wednesday’s deluge of data, including PCE prices, arguably bolstered the case for a hawkish pivot.

The minutes noted the obvious — the inclusion of statement language suggesting that the initial pace of tapering would likely remain appropriate in subsequent months was meant to indicate that the Fed would cease adding to its holdings of securities by the middle of 2022.

The word “inflation” was mentioned 80 times. “Bottleneck” six. “Disruption” five.

Participants expected “robust growth” in 2022, thanks largely to vaccine progress and easing supply chain constraints. Notably, some officials suggested the labor force participation rate may be permanently impaired. The key paragraph in that regard reads,

While recognizing that labor market conditions varied significantly across the country, some participants cited a number of signs that the US labor market was very tight: These included data on quits, job availability and stronger rates of nominal wage growth reflected in the recent rise in the employment cost index, as well as the readings provided by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s Labor Market Conditions Indicators. A number of participants observed that the labor force participation rate remained well below the level reached before the pandemic. Several participants judged that labor force participation would be structurally lower than in the past, and a few of these participants cited the high level of retirements recorded since the start of the pandemic.

That recalls the discussion from “What If The Workers Aren’t Coming Back?“, in which I not-so-gently observed that “no longer are workers begging to be hired and willing to accept a pittance for the ‘privilege’ of running full speed in a hamster wheel all day.”

Instead, workers are quitting in record numbers, leaving employers begging to hire and pleading with existing workers to stay on. No matter the cost (figure below).

In the the bank’s 2022 economic outlook, Goldman wrote that participation “is likely to remain below the pre-pandemic demographic trend, with most of the early retirees — who account for almost 40% of the remaining gap — staying out, and even some of the younger and middle-aged workers staying out too.”

Somewhat ominously, the November minutes noted that “District contacts continued to report difficulties in finding and retaining workers and that, in addition to offering higher wages, businesses were turning to increased use of automation.” Bring in the robots!

Still, some Fed officials viewed the dislocations as temporary, suggesting that labor supply was “being depressed by pandemic-related factors such as disruptions related to caregiving arrangements and noted that the importance of such factors would likely diminish as economic and public health conditions improved further.”

The discussion around inflation wasn’t what one might call “humble,” but it did plainly suggest that policymakers are in the process of “refining” their views, to employ a euphemism.

Inflation pressures, participants said, “could take longer to subside than they had previously assessed.” Further, the Delta variant “intensified the impediments to supply chains and helped sustain the high level of goods demand, adding to the upward pressure on prices.”

And then there’s energy. And wage growth. And surging rents. All of those forces “added to inflation” too and “some” participants pointed out that price increases “had become more widespread.”

“Many” participants noted that “average inflation already exceeded 2% when measured on a multiyear basis.” Those officials also cited “businesses’ enhanced scope to pass on higher costs to their customers, the possibility that nominal wage growth had become more sensitive to labor market pressures [and] accommodative financial conditions” as factors which “might result in inflation continuing at elevated levels.”

As for the prospects for an accelerated taper or an “early” liftoff, the minutes said “various” officials suggested the Committee “should be prepared to adjust the pace of asset purchases and raise the target range for the federal funds rate sooner than participants currently anticipated” should inflation refuse to abate.

Finally, the Fed is apprised of how the current situation affects everyday people. The minutes described the Fed as “attentive to the sizable increase in the cost of living that had taken place this year and the associated burden on US households, particularly those who had limited scope to pay higher prices for essential goods and services.”

“You may know this,” but “there’s a pretty substantial tent city” that Powell drives through “on the way home from work.”