Cognitive dissonance doesn’t have to be distressing, although it often is.

You can harbor inconsistent beliefs and exist in a state of relative psychological comfort as long as you acknowledge the inconsistencies.

Reconciling incongruous beliefs and forecasts may seem like a desirable (even noble) exercise, but it can also be painful to the extent some conflicts aren’t reconcilable. In that case, you’re forced to admit that one (or more) of your beliefs must be wrong if the others are right. Then you have to choose which ones to keep and which ones to jettison, or else revert to cognitive dissonance.

Such is the plight of Wall Street’s research departments by November, when economists and strategists responsible for covering disparate regions and asset classes are forced to craft a semi-coherent global narrative for the year ahead. As Morgan Stanley’s Vishwanath Tirupattur somewhat euphemistically put it in a note dated November 21, the process entails “weeks of deliberation and spirited debate.”

Getting everyone on the same page is arguably more important than it used to be. Although I’m not sure Tirupattur meant to say anything profound, he was certainly correct to assert that we live in a “highly inter-related world, where everything effectively affects everything else.”

Morgan’s outlook for 2022 was complicated by the bank’s reluctance to bring forward Fed liftoff. They still expect the first rate hike in 2023, which is somewhat incongruous both with market pricing and with a generally constructive take on the domestic economy. Tirupattur acknowledged as much, writing that “our economists’ view that the Fed will wait until Q1 2023 to make its first rate hike, despite their projection that US unemployment will fall to 3.6% by end-2022, was hotly debated.”

You might recall that the bank also grappled with the 2023 liftoff call while debating the outlook for stocks. “At face value, our global macro forecasts suggest a continued benign backdrop for equities in 2022 with strong nominal (and real) GDP growth, moderating inflation through the year and no rate hikes from any of the G3 central banks,” Mike Wilson, Graham Secker and Jonathan Garner wrote last week.

Read more: Why US Stocks Will Lag The World In 2022

While their cautious take on US shares is predicated on the prospects for margin erosion, higher yields and waning profit momentum, the sequencing the bank expects in rates and FX is important. Or at least it is when it comes to reconciling some of the readily apparent cognitive dissonance in Morgan’s outlook.

Tirupattur addressed the contradictions head on. “The forecasts our strategists presented were more cautious than our economists’ expectations of strong growth, moderating inflation and patient central banks, leading us to debate whether this is a set-up for “Goldilocks’,” he wrote, before posing the following question: “Didn’t our economic forecasts imply the best of all possible worlds and, as such, a better environment for markets?”

In short, the answer is “yes,” they did. But some of the nuance is in the notion that markets are wrong about the Fed, and thereby wrong about real rates and the dollar, and will ultimately be forced to “come around,” so to speak, on a delay.

“Markets first price in a more hawkish Fed outcome,” Tirupattur wrote, summarizing the gist of the sequencing thesis that ties the bank’s 2022 outlook together. That will initially lead to bear-flattening, higher real yields and a stronger dollar.

Obviously, we’ve already seen some of that. The dollar is on a hot streak and the curve has flattened. But real yields are still near record lows, which (partially) explains why equities are still buoyant despite the “policy mistake” signal from the curve and a stronger greenback.

It “may not be immediately apparent” to markets that central banks are destined to remain dovish, Tirupattur went on to explain, recapping why the bank’s equity analysts see potential “challenges early in the year.”

Ultimately, though, the Fed won’t hike in 2022. That’s because, again according to Morgan’s economists, PCE will cool off and the labor force participation rate will pick up. Obviously, that’s precisely what the Fed is hoping for.

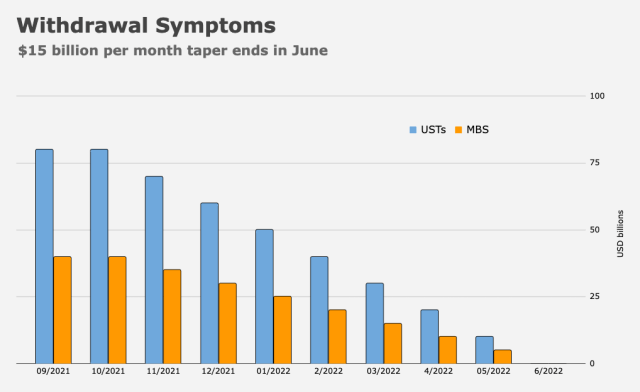

The bank put a pretty specific timeline on that benign macro outcome, writing that “the market could see more support for these expectations as soon as March and no later than June next year.” In other words, just in time to avoid a scenario where the Fed feels compelled to consider a rate hike once the taper is completed (figure below).

After that, Tirupattur said, the market could “shift to concern that the Fed may be too dovish,” leading to bear-steepening, higher breakevens and a weaker dollar.

Note that Morgan isn’t alone in suggesting (tacitly or otherwise) that the Fed won’t be as quick to abandon the commitment to the labor market as many traders and analysts seem to believe. And if headwinds to full employment persist while inflation moderates as supply chain bottlenecks work themselves out in the new year, analysts and traders betting on two full hikes in 2022 could be forced to adjust their expectations rather dramatically.

As for Biden’s decision to keep Powell as Chair, Morgan’s economists “do not see material changes to policy outcomes” tied to the composition of the FOMC.

Those analysts & strategists have their work cut out in this headless chicken market, especially during tax lot selling season. Along with the now normal daily rotations in and out of favor.

H-Man, no one wants to talk about Powell raising intererst rates before the mid-terms.

Actually lots of people want to talk about it. That’s all anyone was talking about today — pulling forward hikes and Eurodollars selling off.

The Goldilocks outcome is probable at least through the summer. It just won’t “feel” very Goldilocksish as volatility will likely be high, with large swings in both directions with a amplitude and swiftness unlike the market has ever seen. Well, except maybe H1 2020. It won’t likely be as deep a dive as 2020 without some exogenous event, but fast down 8-16% followed by fast recovery is likely to happen multiple times next year. It will give a whole new meaning to by the dip as the dips will get much bigger. If things stay on track as they are fiscal and monetary policy wise, Q4 2022 at this point is a cause for concern as the dip might keep dipping for a while. Of course, I’m just guessing like everyone else.