During the vicious, tech-led selloff that wiped away a fleeting, post-FOMC bounce in US equities, Cathie Wood’s star-crossed flagship fund suffered its worst one-day decline since the onset of the pandemic.

The 9% single-session drop on May 5 brought the product’s YTD decline to more than 50% (figure below).

More notable, perhaps, was the lamentable reality that every holding in the Ark Innovation ETF was negative in 2022 with but a single exception: A $4 million cash allocation. It’s returned 0.03%.

Despite the fund’s 73% drawdown (from the highs through midday Friday), at least some investors seem to believe Wood can recapture the magic. ARKK took in some $600 million on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday combined.

Wood’s is an Icarus tale, and I’ll be the first to concede that recent criticism, explicit and that implied by breathless media coverage, is gratuitous. However, Ark’s stark reversal of fortune encapsulates a dynamic years — even decades — in the making. Because of that, it can’t be ignored.

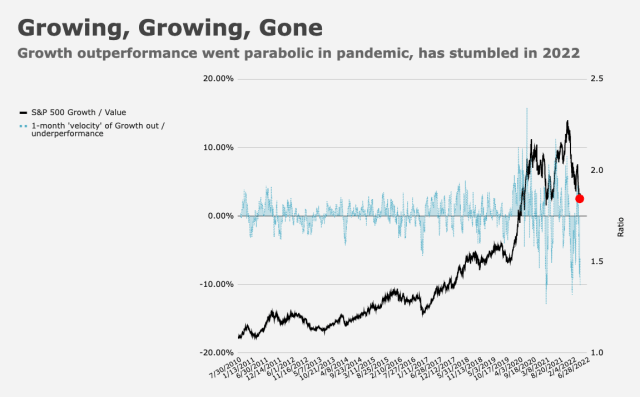

Regular readers are familiar with the story. Over the past dozen years, a macro regime colloquially known as “slow-flation” (or “Goldilocks”) favored growth stocks, which benefited handsomely from the plausible deniability subdued inflation afforded to central banks. As long as price pressures were muted, policymakers had carte blanche to ease in pursuit of better growth outcomes, unencumbered by the kind of inflation many critics insisted was inevitable as a result of copious “money printing” and generalized monetary largesse.

Of course, there was plenty of inflation. Just not in the real economy. Rather, in financial assets of all sorts, including and especially mega-cap tech stocks and growth (as a style), which traded on higher and higher multiples as rates remained glued to the lower bound and bond yields trekked to zero (and below).

This inflated the market caps of behemoths like Apple, Google, Facebook and Microsoft, until US equities became one giant long-duration bet, the size of several major economies. The figure, below, shows where things stood prior to the recent unwind.

The proliferation of passive investing and the tendency for the tech titans to become synonymous with multiple factors and styles used to construct smart beta ETFs, meant that more and more money flowed into the same handful of names, levitating the broad market which, paradoxically, became less “broad” all the time as a result of big-cap tech’s swollen market cap.

It’s difficult to beat a benchmark that rises every year, especially when the inexorable ascent has the backing of benefactors with printing presses and when tracking benchmarks is essentially costless thanks to giants like Vanguard and BlackRock competing to drive fees lower. For active managers, the only way to outperform was to simply buy the same stocks, only with leverage.

“Fundamentally, and macro-wise, PMs have been hiding in ‘leveraged long-duration’ equities proxies for a decade,” Nomura’s Charlie McElligott said. “Survivorship bias meant that in order to thrive — to outperform benchmarks and gather more assets — you simply built a ‘Doomsday Momentum Machine’ that kept piling into these secular growth names at nosebleed valuations, which were being justified by absurdly low rates through ZIRP, NIRP and LSAP / QE policies around the globe,” he added. At the same time, that bent entailed being short (de facto or even outright) anything that even looked like cyclicals.

The Achilles’ heel in all of this was the macro regime or, more to the point, the tail risk that it might suddenly shift in favor of hot nominal growth and high inflation. Such a conjuncture would force central banks to withdraw liquidity, raise rates and abandon forward guidance in favor of reclaiming their independence, not from any political threat, but from markets, to whom policymakers were beholden thanks to an accumulated addiction liability.

That tail risk — a shift in the macro regime — was realized over the past two years, as the pandemic, and then, subsequently, the war in Ukraine, disrupted supply chains, shifted labor market dynamics in unexpected ways, pushed up commodity prices and threatened to permanently undermine globalization, the very core of the multi-decade disinflation.

In addition to the acute human suffering brought about by COVID and the war, there’s a policy tragedy embedded in all of this. The initial response to the pandemic was designed to avert deflation and economic depression, the opposite of what we have two years later. In our zeal to halt the spread of a virus we didn’t understand, we shut down the global economy and printed money — “bridge liquidity,” as Steve Mnuchin famously dubbed it.

With everyone locked indoors and both the monetary and fiscal spigots open, long-duration bets not only continued to flourish, but in fact took one final, glorious leg higher as life (and spending) was channeled through so-called “stay-at-home” stocks. Those stocks were, in almost all cases, tech shares of some kind, whether mega-cap favorites like Apple and Facebook, cloud plays, delivery apps or a company peddling (and pedaling) web-enabled exercise bikes. The figure (below) is a rough illustration.

The final push higher for growth shares set the stage for an even bigger fall once the macro regime reversed course, starting with the approval of multiple effective vaccines.

It took a while, but the payback is showing up everywhere. In Netflix’s stunning prediction for two million lost subscribers, in Amazon’s allusion to a burgeoning overcapacity problem and, most recently, in a harrowing plunge for E-Commerce names.

Importantly, it’s not just a business fundamentals story. There’s a mechanical aspect. As rates rise (a function of the shifting macro regime), speculative corners of the market de-rate. That valuation compression works its way from the outside in. It started in Q1 2021 with “hyper-growth” shares, eventually came for crypto and, finally, for the Nasdaq 100 in April, when the benchmark fell 13%, the worst monthly decline since 2008 (figure below).

The 100 most expensive S&P stocks have de-rated sharply in 2022, from a 26x premium versus the rest of the market all the way down to a 16.1x premium which, you’ll note, is still slightly above the long-term average.

McElligott described a commingling of “idiosyncratic COVID impacts,” such as supply chain disruptions and, later, a massive release of pent-up demand, with a policy response defined by an experiment in overt monetary-fiscal partnerships. That, he said, collided with “a disaster scenario for commodities” creating a situation so out of whack that “you can’t even make it up at this point.”

As detailed last week in “Mispriced Duration And The ‘Otherside’ Of Rising Rates,” everyone is suddenly coming to terms with how all of the above fits together. It’s been a painful reckoning for most, and it’s not over.

The “3 Ds” came to be viewed not as a macro theory, but rather as something akin to a natural law. Structural disinflation was seen as a given — a fact of economic life.

“As I’ve said my entire career, inflation is the volatility catalyst in a world that’s been conditioned for lazy duration longs fueled by the ‘Goldilocks’ economic backdrop which created and perpetuated a wholesale investor cynicism towards even the concept of ‘inflation,'” McElligott said Friday. “And here we are.”

H or anyone, have you seen any analysis of what rate + growth scenario the market is currently discounting, or sensitivity tables for what market valuations are implied by what scenarios? I imagine the strategists have their juniors busily cranking out that sort of work.

Great summary, H. I still wince, though, every time we succumb to the temptation to compare equity market caps with country GDPs given the wholly different kinds of measurement they represent. Call me a purist.

Yeah, but people love that chart. As a general rule, the more “apples to oranges” a chart is, the more people like it. It’s an extension of the public’s penchant for escapism. The more detached from any kind of reality something is, be it a chart or especially a narrative, the more appealing. It’s unfortunate.

The statistic that gets me even more is the one that compares the total notional value of derivatives from the largest global banks to annual world GDP, putting the ratio of derivative value at over four times total global annual GDP. Somehow all that paper feels a bit like the part of the world’s oceans that we know nothing about.

H-Man, regrettably there is no one on deck who has any experience in fighting inflation. So it becomes an exercise in reading manuals from previous episodes or simply winging it. It seems we are dabbling with both prescriptions while relentlessly holding onto the belief, something will work. By the time we figure out what works, the ship will probably be underwater and it will be time to build a new vessel.

I was around in the 70s and 80s. As I recall, back then we fought inflation by printing “whip inflation now” bumper stickers. Oh– we also raised interest rates through the roof. My father took me to open my first checking account in 1980. It paid 12% interest.