A consensus is forming around the notion that the Fed is on the brink of tightening the US economy into a slowdown.

The thesis isn’t complicated. The fiscal impulse is on the wane, consumers are anxious about inflation, a new virus variant threatens to bring about another winter COVID wave and Fed officials are almost uniformly in favor of an accelerated taper in order to make rate hikes possible as early as Q1 2022.

The combination of those factors argues for slower growth. The Fed is caught between a rock and a hard place. Jerome Powell’s decision to publicly jettison the “transitory” characterization of inflation was the clearest signal yet that the Fed now believes policy is behind the curve. The Committee wants to reestablish its inflation-fighting credentials. And the market is betting it’ll try (figure below).

Note that the ramifications for equities are different in an environment defined by another COVID wave and tighter policy compared to 2020, when QE was in full swing and the Fed “wasn’t even thinking about, thinking about” raising rates, to quote Powell’s famous quip.

The hyper-growth trade that prospered last year is imperiled by the prospect of higher macro volatility (i.e., unpredictable and possibly unanchored inflation) and higher real rates associated with the Fed’s pretensions to tightening and/or the mechanical read-through of falling breakevens as market-based inflation expectations reflect the odds of a policy error and slower growth. Perennial secular growth winners and sundry “high-fliers” are staring at a “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” situation.

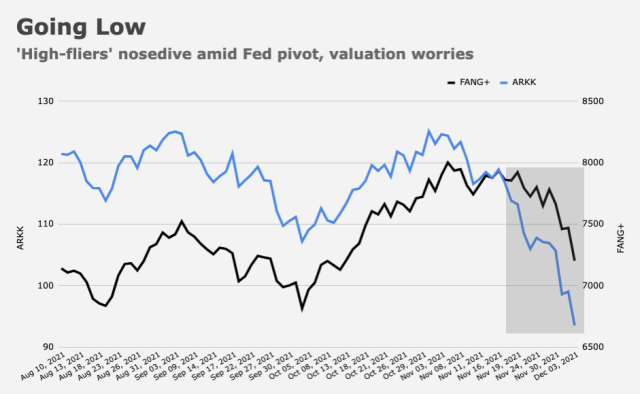

That’s being reflected in the FANG+ index, which is (basically) in a correction, but even more acutely in Cathie’s ARKK, which has been crushed (figure below).

Facebook (Meta) is on the brink of a bear market.

While many would view it as comeuppance if some of the priciest, more speculative growth shares collapsed, a drawdown in mega-tech imperils the benchmarks. Concentration risk, you’re reminded, has never been higher. If circumstances conspire to undercut tech at a time when cyclicals, value and various re-opening expressions can’t take the baton because they’re weighed down by COVID concerns, there’s little that can support the market.

That’s conceptually similar — and inextricably linked — to the risk associated with bonds at a time when macro volatility may be set to rise sustainably. Mega-cap tech morphed into a safe haven over the last several years thanks to predictably strong revenue growth and the ongoing digitization of the human experience. Those trends were amplified by the pandemic.

At the same time, secular growth benefited for the better part of a dozen years from the “slow-flation” macro environment which was defined by subdued inflation and falling bond yields. Growth shares and bonds were part and parcel of the so-called “duration infatuation.” A never-ending rally left both overvalued.

The provision of trillions upon trillions in liquidity turbocharged the dynamic (figure below), as did the epochal shift to passive investing. (Think: Dollars plowed into index funds tracking benchmarks increasingly dominated by the same five or six companies and the proliferation of smart-beta and factor products dominated by many of the same names.)

Now, the macro environment is shifting, and there seems to be no way out.

Although tech would theoretically benefit from growth worries, falling bond yields and a bid for “stay-at-home” stocks, a hawkish Fed and tighter financial conditions could prompt a de-rating regardless.

If Omicron creates additional supply chain frictions and stokes more goods demand (versus services), the read-through for inflation (higher for longer) could prompt even more aggressive action from the Fed, even if the labor market sputters.

If, on the other hand, Omicron proves to be mild, we’re back to pondering higher growth, demand-pull inflation, higher yields and a Fed that’s still hawkish.

There appears to be no good outcome for hyper-growth shares.

I should note that quality growth will always be relatively resilient and my own reservations about Meta notwithstanding, I still struggle to conjure a real bear case for FAMMG that goes beyond a simple (i.e., healthy) de-rating.

Coming full circle, BofA’s Michael Hartnett thinks markets may be a bit of ahead of themselves, even if the narrative will generally be proven correct. “The zeitgeist is ‘Fed tightening into slowdown,’ and it will — eventually,” he wrote. “But the economy ain’t slowing yet, and the Fed hasn’t even started tightening.”

Hartnett continued. “Strong data over the next 3-4 months will mean inflation, a much more aggressive Fed, a higher terminal rate and higher real yields,” he said. That’s “negative for tech.”

I guess we will find out what kind of Man JPowell truly is. He didn’t hold up so well in December 2018.

Shouldn’t Modern Monetary Theory have the answer for the abundance of dollars it creates?

The answer is to raise taxes so as to pull dollars back out of the economy.

That would only be appropriate if the economy was at full resource utilization, which it is not. Inflation is not a monetary issue. It is always a supply issue. An economy with slack will increase supply to meet demand. If there was no slack, then taxing back demand would be appropriate. Taxing now or cutting spending (same thing) would remove support and start a recession.

So what’s the fuss all about if it’s so easy…just tax away the inflation right?

The Fed operates monetary policy which does not have as much of a punch as fiscal policy (spending currency into existence). QE is NOT “printing money”. It is swapping already existing assets (Treasuries and MBS) for free “green dollars”. Treasury spending into the economy creates new dollars that very quickly end up in corporate profits or in private savings. That money creation that is not taxed back, remains as private sector surplus. The physical is what really matters, and that is not going to tighten.

It just occurred to me, isn’t QE money laundering? Isn’t that illegal?

While Powell may pivot back to a dovish stance it is not going to happen until their is broad base evidence in soft and hard data, so months away at a minimum. Once central bankers make a shift, they are unlikely to quickly throw that change under the bus, barring at 1987 crash scenario. One other thing that reading this article made me think about is the Apple and other long duration stocks are touted as candidates for a “bond replacement strategy.” This reminds me of the time into the lead up to the GFC how Wall Street was full of powerpoints proving commodities were a diversifying asset because the correlation to equities and credit was low. If you look back to 2008 or even 2014-2015, it is clear that that Apple as a bond replacement is one of the silliest ideas ever.