A dozen years of “money printing” and debt monetization created a lot of things, but inflation isn’t one of them.

Well, that’s not true. Inflation is one of them, just not the kind of inflation central banks would like to see.

There’s been plenty of inflation in financial assets. And, obviously, there are myriad instances of exponentially higher costs for crucial things like healthcare and education in the US, but at least some of that is explainable by government ineptitude and dynamics not directly attributable to developed market central banks.

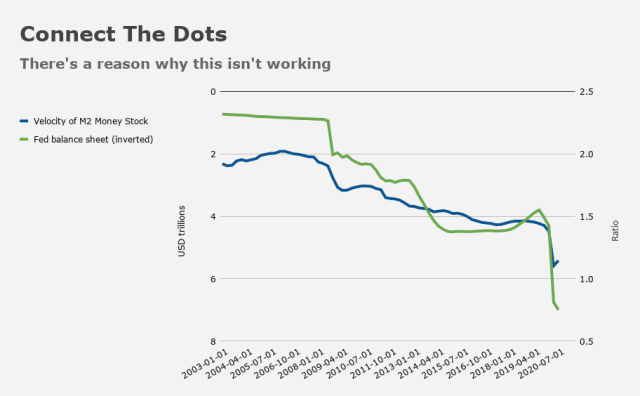

What accounts for the apparent disconnect between, on one hand, trillions upon trillions in asset purchases and generally free money, and, on the other, lackluster inflation? One answer is the middleman. Because everyone involved insists on maintaining the charade that says QE isn’t debt monetization, we have to insert an intermediary. The result of that arrangement can be illustrated using the familiar visual (below).

I suppose some of the “blame” lies with the demand side of the equation, but the fact is, the largest US banks are dedicating less and less (as a percentage) to loans over time.

There are myriad factors that explain the trend, and yet one can’t escape the obvious. Banks are hoarding cash and government-backed securities and lending less into the economy.

Bloomberg summed up the situation earlier this month. “Lending has faced scrutiny during the pandemic as banks retrench, and small businesses and households find it harder to obtain reasonably priced credit,” an article dated February 8 said. “Loans began accounting for less than half of big banks’ books for the first time last May, and in the 35 weeks since then lending has fallen to a fresh low 21 times.” If you’re wondering what that looks like, you’re in luck (figure below).

Little wonder, then, that all this “money printing” doesn’t manifest in real economic outcomes.

At the risk of oversimplifying complex dynamics, the sharp decline in the figure (above) suggests that for all the boasting banks did last year about their efforts to bolster beleaguered households and businesses, a 30,000-foot view tells a different story.

Is this ever going to change? Well, possibly. Some continue to suggest that once the pandemic abates, quite a bit of this liquidity could be unleashed. When you consider the prospect that elevated savings levels (e.g., due both to consumer retrenchment and stimulus checks) could simultaneously be drawn down once employment in key areas of the economy bounces back (assuming it does bounce back), you can conjure an “interesting” (to employ a euphemism) scenario.

“The velocity of money will rise,” BofA’s Michael Hartnett wrote this week. He noted the $3.5 trillion US budget deficit and $13.3 trillion in global central bank liquidity, before observing that “as in pretty much every one of past 12 years, policy stimulus in 2020/21 continues to flow directly to Wall Street not Main Street.”

That has, of course, exacerbated the wealth divide. It’s “inciting historic wealth inequality via asset bubbles,” Hartnett went on to remark, on the way to saying that, “we expect rising velocity of people (vaccine > virus) in 2021 to engender [a] rise in the velocity of money, inflation mutation from Wall Street to Main Street, [and a] pop in the nihilistic bubble.”

As you can see, Hartnett “goes there” (if you will), where that means alluding to one of the scariest possible historical examples.

“Post-WW1 Germany [is the] most epic, extreme analog of surging velocity and inflation following [the] end of war psychology, pent-up savings, and lost confidence in currency and authorities,” he said.

Is that what’s coming in the US? In a word: No. And that’s not Hartnett’s point (I hope).

Rather, he simply noted that “we believe 2020 marked [the] secular low for rates/inflation, and [the] 2020s [will] likely [be a] decade of inflation assets > deflation and real assets > financial.”

Draw your own conclusions.

The US savings rate is currently somewhere around 7-8%. Not that the US would ever go as far as Japan, but their savings rate is about 30%.

As our country ages, with a lower birthrate, it is inevitable that the older portion of the population will travel, dine out, and spend less.

What will happen to our savings rate post-pandemic? Even if the savings rate stays high, that savings has to get invested somewhere.

“Banks are hoarding cash and government-backed securities and lending less into the economy.”

A decade or two ago this trend rested mostly with the smaller banks (under 100mil in assets) who could borrow cheaply and invest for a nice profit in USTs. No risk and the owners could just book nice returns with virtually no risk. Now, it appears that the larger banks have discovered the same game. Pay nothing on savings accounts, make only the safest loans (mortgages granted only if they are FHA protected or can be readily sold), collect fees for mortgage servicing, underwriting, investment advisory services, etc. The less connected these banks are to the real economy, the better. It works for the little guys, why not for the big ones.

Perhaps one reason banks might hoard cash, is because people hoard cash — maybe that’s related to fear about economic stability. The 2-yr Treasury continues to affirm the concept that future growth will be non-existent for years. In addition, the latest spike in speculative excess in short-term penny stocks is somewhat related to lower global corp earnings, low dividend yields, valuation — and — a fair amount of unemployed people and the lingering pandemic that may become even more challenging in a few weeks due to mutating variants. As much as everyone wants rapid positive change it’s still likely that the next few months will be very challenging (for everything).

In the post trumpian economy, it’s unlikely any prior normalicy will suddenly fall into place and more than likely extreme weirdness will be the new norm. Hoarding seems wholesome and a logical strategy for hedging non-linear economic dynamics.\

This morning I was looking at valuations and came across the new and improved Shiller Excess CAPE yield, which apparently tells us that stocks are not overvalued but attractive — but it kind of fits in with Marko Kolanovic’s thinking and goes against the grain of hoarding and fear — as usual, anxiety loves conflicting choices!

In another nod to hoarding (or not) these following concepts are interesting and add a few brush strokes to potential structural changes underfoot. I’m stimulated by the idea of a labor force engine that runs on fewer cylinders, sorta like the end of the V8 muscle cars from the 60’s and 70’s to everything after — and now generational Tesla-type evolution and AI growth acting like a new layer of cement being poured over a dead labor market.

The ECB Moves Towards Pre-GFC Peak ‘Favorable Financing Conditions’

Feb. 08, 2021

Adam Whitehead

“What companies have done with the borrowed funds is dubiously countercyclical at best. They have certainly not hired more workers. Presumably, some of the borrowed funds have been used for the capital substitution of labor.”

Some of the companies’ borrowed funds will have been used for financial speculation. Some of this financial speculation will have been in themselves. Some companies will have re-leveraged their operations and balance sheets, at much lower rates of interest, thereby giving them some extended cash flow longevity and profitability. No doubt, they will also have borrowed to buy back their own shares, thereby, falsely painting an accounting picture of business health.

Low interest rates and easy money have, thus, created a potential double-whammy of overcapacity and innate financial instability, in the corporate sector, through companies that have scaled-down operationally whilst preserving their accounting appearance of profitability. This behavior will be sold to investors as efficiency and productivity gains. In aggregate, it is the same as running an engine on fewer cylinders.

That bit, connects to some thoughts from Ed Yardeni (February 10, 2021)

On a y/y basis through January, the labor force is down 4.3 million, with women accounting for 58% of the drop. Many no doubt had to quit jobs to take care of children whose schools were operating online only. Also, many individuals in the high-risk age group may have decided to retire early, especially those in face-to-face jobs like teaching.

We can see that in the JOLTS report, where the number of quits jumped from last year’s low of 1.9 million in April to 3.3 million in December (Fig. 11). The quit rate is especially high in the leisure & hospitality industry (Fig. 12). Usually quits rise during good times as people find better jobs. This time, many of the quitters may be dropping out of the labor force.

(9) Bottom line. The data do support Summers’ notion that the government’s unemployment benefits were helpful at first but now may be contributing to a shortage of workers and may continue to do so under the Biden plan.

There’s been loads of “inflation” over the last 30 years. It’s just not measured qualitatively. Anything (apart from tech) that you buy today for the same price as twenty years ago Is substantially inferior in quality. If you want to buy the same quality as twenty years ago it will cost multiples of the price from said period. The whole p* needs to be recalibrated.