The last time I checked up on Guggenheim’s Scott Minerd, the economic fallout from the coronavirus epidemic was shaping up to be worse than he anticipated.

“The economic drawdown is going to be bigger than I originally thought”, he wrote, some three weeks back.

As noted, that was quite the statement. After all, this is the same Scott who, on February 27, sat across from Joe Weisenthal on Bloomberg TV and told a national audience that COVID-19 was “possibly the worst thing I’ve ever seen in my career”.

Read more: Scott Minerd Woke Up On The Armageddon Side Of The Bed This Morning

Credit where it’s due: Minerd was right. Just days after Scott shocked Weisenthal and Scarlet Fu with his dark vision for the future (delivered, again, on live television), things fell completely apart.

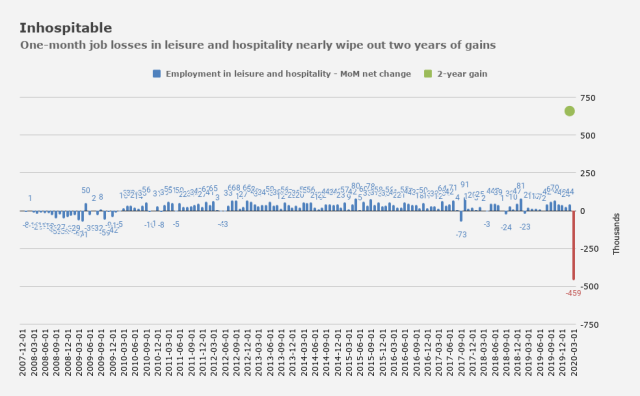

In the three weeks since his last outlook piece, the US economy has all but evaporated. The 26 million jobless claims filed over the past five weeks effectively wipe a decade of net job creation off the board – plus 5 million.

In his latest missive, Minerd cranks up the dour prognosticating and, at this point, it’s nearly impossible to argue with everything he says, even if you want to say the hyperbole is… well, hyperbolic.

“The damage to the household sector is so severe that it is going to impair living standards for most of the decade”, he declares, in an especially foreboding piece published Sunday.

Minerd reminds you that around half of Americans came into the crisis with less than $500 in savings. For those folks, the psychological impact of an abrupt recession will linger for years, with “long-term negative repercussions on consumption”. It isn’t likely, he says, that America’s shell-shocked middle class is going to rush out to buy a car or even to see a movie once things begin to normalize.

From a demographic perspective, Minerd warns that “young, hourly workers in lower-paid service industry jobs are bearing the brunt of economic pain”, which is problematic because those are “the people least able to deal with an interruption to income”.

That setup (in which the most vulnerable are the hardest hit) “will compound the economic pain from layoffs as consumption falls even more sharply”, Minerd predicts.

It’s certainly true that the wealth divide and the increasingly inegalitarian nature of American society means the middle class was ill-prepared for a modern day depression (assuming it’s possible to be “prepared” for a depression).

A March 30 poll conducted by CreditCards.com shows that 59% of Americans with credit cards came into the coronavirus pandemic with credit card debt. Respondents were asked to identify what kinds of expenses and purchases they put on their cards. The results were not particularly encouraging.

More than a quarter of those polled said they put “day-to-day expenses” on the plastic. 13% said medical bills landed on their cards. 12% paid with a card when having their cars repaired.

Clearly, the sudden loss of a job would be potentially ruinous if you were already putting everyday expenses on your credit card.

Guggenheim’s Minerd doubts whether the bailout checks are going to be particularly effective when it comes to providing “bridge liquidity” (as Steve Mnuchin put it) for those who need it most.

“The increase in unemployment benefits was a phenomenally good idea but sending checks for $1,200 to households does very little to solve the problem, because these payments are not targeted”, he said Sunday, adding that “many people who are working and doing fine are going to get a check they don’t need [while] people who really could use the money need more than $1,200”.

As far as the government’s flagship assistance program for Main Street (the Paycheck Protection Program), Minerd sees a problem – specifically, he worries that while forgivable loans will help keep workers on payroll now, the prospect of a long-term hit to demand will make it difficult for businesses to sustain full employment.

Of course, no critique of the policy response to the current crisis would be complete without a generic “moral hazard” argument centered around the Fed’s decision to buy IG and HY bonds. Minerd doesn’t disappoint in that regard.

First, he (correctly) points out that it was a decade of low rates and central bank largesse which encouraged management teams to gorge themselves on debt in the first place. That leverage (in some cases incurred in the service of plowing the proceeds from debt sales into EPS-inflating buybacks) meant corporate America came into the crisis in a precarious situation.

“Fed purchases cannot turn bad debt into good debt”, Minerd says, adding that “a buyer who is not careful can mistake Fed liquidity for credit strength and pay the price down the road when downgrades and defaults start in earnest”.

Next, he delivers the goods with a harsh assessment of what the future holds for price discovery and free markets. To wit:

If you go back 10 years to when the Fed started quantitative easing (QE), the debate was about how long QE would last and when would an exit strategy begin. I remember saying to people at the time, “The Fed will never be able to end quantitative easing; it’s here forever.” And now the new Fed backstop for credit for corporate America is here forever. My fear is that this policy blunder will have long-term implications for our society. The Fed and Treasury have essentially created a new moral hazard by socializing credit risk.

I have some potentially distressing news, folks. The privatization of profits and socialization of losses isn’t “new”, as Minerd claims. In fact, it’s a fixture of American capitalism. When things are going well, the rich reap the rewards. When they aren’t, taxpayers ride to the rescue.

Ultimately, Minerd frets that “the United States will never be able to return to free market capitalism as we knew it before these policies were put in place”.

And just when “free market capitalism” was working out so well for everyone…

The irony, of course, is that central bank policies instituted in the wake of the last crisis have turbocharged inequality in America by inflating the value of financial assets concentrated in the hands of the wealthy.

This time won’t be different in that regard.

Beautifully written and more aligned with the reality that people are not going to rush out shopping like it’s Xmas. The long term hit to global GDP hasn’t been factored appropriately by any rocket scientist on Earth!

yup, basically 1% are winning and 5-9% are treading water and everyone else is bleeding or being destroyed. The situation has been eroded for decades and this crisis has fractured it permanently. There is no patching things back the way they were, by the time we have dealt with the health issues the economic damage will total. I certainly have little doubt that anything close to egalitarianism is returning soon, but those running the show had better be very careful before declaring “let them eat cake”.

The question of price discovery is key. In a pre-QE4ever, pre-COVID world, Tesla, Netflix, Uber, Lyft, Wayfair, the banks, the airlines, cruise lines, casinos, and frackers would have been written off as uninvestable. But in a world where big-cap losses are socialized, how much a company loses doesn’t matter? And if losses don’t matter, than share price is meaningless.

Good article and these first 3 comments are excellent.