Headed into 2020, the combination of the Sino-US trade truce and a dovish Fed set the stage for the dollar to extend declines logged in the fourth quarter, providing a fillip to the reflation trade and bolstering global growth in the process.

Or at least that was the thinking for some market participants. But you know what they say about the best-laid plans.

The narrative made sense. The “Phase One” trade deal and dozens of rate cuts from central banks around the world ostensibly laid the groundwork for the global economy to play catch-up to Donald Trump’s MAGA machine. As the economic performance gap between the US and the rest of the world closed, one pillar of dollar strength would crack. Meanwhile, the Fed all but promised to persist in messaging that suggested the bar for rate hikes is impossibly high, while the bar for additional cuts is fairly low.

Fast forward nearly two months into 2020 and the greenback is on pace for its best start to a calendar year in half a decade.

There’s no mystery here. The coronavirus outbreak suggested the global economy was on the verge of succumbing to an “out of the frying pan and into the fire” dynamic. No sooner had the trade war abated than a new threat to growth and commerce emerged. Because it seems highly likely that the economic fallout from the virus will disproportionately affect ex-US economies, the assumption now is that US economic outperformance will continue, leaving one of the key pillars of dollar strength intact.

Meanwhile, the necessity of policy easing in other locales to offset the assumed deleterious effects of the virus means the monetary policy divergence between the US and its global counterparts could widen anew, even if the Fed continues to deliver dovish forward guidance.

For evidence of that, look not further than the euro, which is sitting near the lowest levels in years after a string of disappointing data suggested the bloc’s economy was stumbling even before the epidemic began to spread across China. The euro-area economy barely expanded in Q4, data out late last month showed. Growth decelerated to a minuscule 0.1% pace QoQ, less than the 0.2% the market was looking for, marking the worst quarter in nearly seven years. France and Italy unexpectedly contracted.

In Germany, the situation is dire indeed. “For the euro-area in particular, the virus shock may extend the streak of weaker-than-expected activity data, raising questions about whether a durable recovery has actually taken hold”, Goldman’s Zach Pandl said Thursday.

“Apart from benefiting from its status of a safe haven, the dollar is also supported by the ongoing expansion of the US economy”, Rabobank’s Piotr Matys wrote this week, adding that recent data has seemingly “confirmed that the US continues to outpace its G10 peers in terms of economic activity [and] it’s worth noting the Bloomberg Dollar Index broke above the downside trendline that capped gains since October [a] constructive technical signal may embolden the USD bulls”.

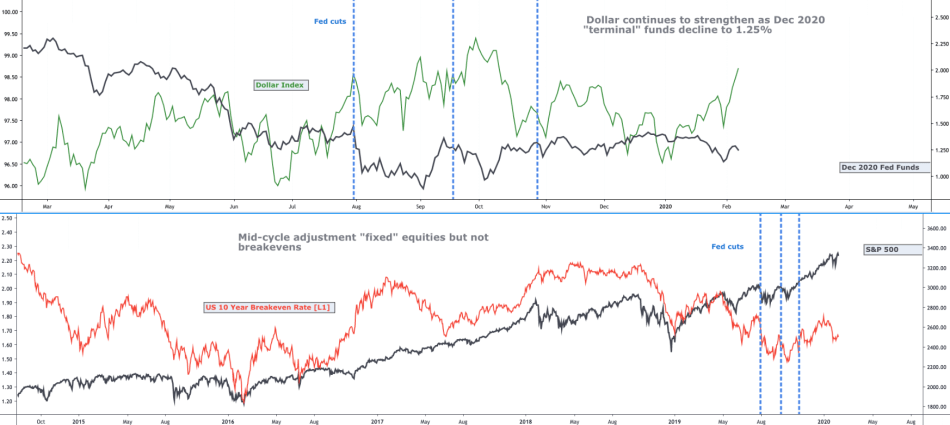

This dynamic is at the heart of some arguments for why the Fed will ultimately be forced to keep easing, perhaps until they hit the lower bound. If they don’t, a stubbornly strong greenback will simply import the world’s disinflationary impulse at a time when a trio of Fed cuts has already failed to reinvigorate inflation expectations.

Haven demand for USD assets amid the Wuhan outbreak only exacerbates the situation.

This is bad news for global growth, folks. As discussed at length here on Wednesday, the current setup is conducive to catalyzing bull flattening in the US curve, which only amplifies the disinflationary signal to markets.

Previously, any negative correlation between the dollar and the curve was due primarily to bear flattening and bull steepening, as a stronger economy raised the odds of tighter Fed policy (stronger dollar) and vice versa (weaker dollar as short rates fall in anticipation of easier policy). Now, that mode has changed. As Deutsche Bank wrote this week, the interaction between the dollar and the curve slope is now “a result of persistent dollar strength and its dampening effect on inflation expectations”.

For their part, Goldman suggests the impact on global growth from the virus will be “10 times as large as a major US hurricane”, and when it comes to the disruptions to work in China, the fallout from the epidemic is set to approximate “the entire US workforce taking an unplanned break for two months”.

A stronger dollar will be both a symptom and an aggravating factor in all of this, creating a non-virtuous loop, something Invesco Asset Management’s Arnab Das reiterated at a conference in Miami recently. “When the Fed shifted gears to easing and cutting rates, all it really did was open the door for everybody else to either cut rates or increase the size of balance sheets, or both”, he remarked. “So the interest-rate differential, monetary-policy differential, balance-sheet differential arguments in favor of a weaker dollar haven’t worked either. Those issues are still going to be there for some time to come”.

This is a great time to recall something SocGen’s Kit Juckes said back in December, before anyone was worried about a pandemic: “The world’s a nicer place when the dollar’s on the back foot”.

Dear H. One of these days, I hope you’ll do a post on why moderate disinflation is a bad thing. I think a lot of Americans, struggling with a dollar whose purchasing power has been falling for decades (inflation), would agree with Annie Lowrey’s diagnosis of the probelm in this Atlantic article: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/02/great-affordability-crisis-breaking-america/606046/

Debt/deflation spiral evokes a paralytic response from central banks especially against a backdrop of high debt loads. One day defaults will fix this but the political appetite for that today seems rather low

I would be interested to read such a post.

As I understand it, the theoretical terrors of deflation relate to goods and services that are somewhat discretionary, meaning you can buy them now or later. If prices are declining, consumers will defer purchases now in hopes of lower prices tomorrow. Deferred purchase -> lost revenue -> lost wages -> lower economic activity. If we had a whiteboard, we could draw that as s downward spiral

They also relate to a scenario where debt service remains fixed while the debtor’s income declines. In addition to being painful for debtors (think borrowers, bond issuers, etc) this could also make creditors (this lenders, bond buyers) think twice about making new loans. Extend that thought to dividend paying companies too.

In addition, deflation is frightening because historically falling prices may be associated with economic contractions, even if causation is unproven.

We don’t have much modern experience with deflation in the US or any other developed country, so there’s some fear of the unknown too. There’s been deflation in specific industries – PCs were getting cheaper every year for a time – but never broadly.

However, prices of goods and of services are affected by different factors and behave differently. Notice that the things mentioned in that Atlantic article are largely services: education costs and healthcare. The one major item that is sort of a good is housing – though housing is also a service, and perhaps real property should be in a third category of “asset”.

Services are largely a product of the domestic economy. College tuition, medical insurance, apartment rent, aren’t being imported from China. The USD level isn’t all that relevant to the price of those services. I don’t know how a stronger dollar would import deflation in my kids’ college tuitions.

These also happen to be purchases that are largely non discretionary. If medical insurance premiums are expected to be cheaper next year, you’re not going to put off buying insurance this year. If rent is expected to be cheaper next year, you’re not going to live under the freeway overpass this year (by choice anyway).

So, deflation in the things listed in the article – which happen to be the things most crushing average families – might not be such a terrifying thing after all. There’d still be losers, especially from housing deflation. The preferable alternative might be for incomes to go up rather than for medical insurance premiums and rents to go down (maaaaybe).

King Dollar also doesn’t have all that much control over the price of those things, as far as I can see.

Anyway, goods inflation has been running much weaker than services inflation for many years now. I don’t have the FRED charts handy but they’re easy to call up. I want to say, from memory, that goods inflation is something like 1% or <1% while services inflation is more like 3-4%?

This begs the question of whether CPI correctly measures inflation as experienced. Don’t know about everyone else, but the vast majority of my personal and business spending goes to services and sort-of-services (college tuition, healthcare, mortgage, taxes, office rents, professional and business services, data and other subscriptions, etc). The rest of my spending is mostly on non-discretionary goods. No new Porsche lately, ha ha. The USD can import all the deflation it likes, it won’t have much direct impact on me or, I’d wager, most of H’s readers. The impact on asset prices could be a different story.