SocGen’s Albert Edwards still believes in “The Great Melt.”

Not the BBC David Attenborough documentary. Rather, the thesis that says overt fiscal-monetary partnerships are inherently inflationary and will eventually “thaw” developed market economies after decades spent languishing in the frozen tundra of Albert’s secular “Ice Age” theme.

By now, everyone should be able to recite some version of the narrative. The pandemic compelled policymakers to respond in something like real-time to the burgeoning crisis. There could be no “deliberation.” Economies were shuttered. All but the most essential businesses were closed. Citizens were ordered to remain in their homes. Healthcare systems were overwhelmed. People were dying.

As in war time, governments simply conjured money. As cash materialized in bank accounts, it dawned on many a previously clueless citizen that government expenditures are not, in fact, “funded” ahead of time. The Trump administration’s decision to delay tax day only underscored the point. No developed nation that issues a respectable currency needs to “locate,” “source” or otherwise “find” that currency when it’s needed. Rather, lawmakers can simply order it into existence, then hand it out to citizens.

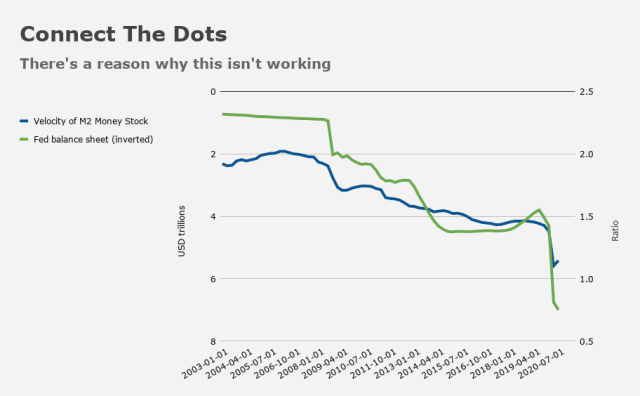

The charade that says outlays are offset by debt was maintained, but simultaneous asset purchases by central banks left little room for interpretation. The various veils that obscured the nature of QE from the general public were lifted. It was impossible to maintain the facade due to the sheer magnitude of the expenditures and the simultaneous expansion of central bank balance sheets. The figure (below) is dated, but it gets the point across.

Some call this progress. After all, we’ve been doing it for years. If we’re going to carry on doing something manifestly absurd in perpetuity, we may as well tell ourselves the truth about it.

QE is just debt monetization at arm’s length. When central bank balance sheets are never unwound (or only partially unwound), there can be no other interpretation. There are no “alternative facts.”

Since the financial crisis, developed markets have been buying debt from themselves. When you consider that “debt” isn’t really “debt” for a currency-issuing nation with sufficient monetary sovereignty, the entire exercise is exposed as a ridiculous, self-referential carousel. One organ of the state creates currency to buy an interest-bearing version of that same currency from another organ of the state. Then, the state spends the “proceeds” from that “transaction.”

It’s not just circuitous, it’s pointless. I’d call it sleight of hand, but it’s not clear who we were trying to fool. Prior to the pandemic, anyone who cared to understand the dynamic understood it all too well. And it’s been obvious for years that inserting a middleman (banks) into the equation was more trouble than it was worth. The falling velocity of money pretty clearly suggested the arm’s-length character of the self-funding scheme was impairing the monetary policy transmission channel (figure below).

Ostensibly “serious” people prefer we preserve at least some version of this ridiculous charade rather than admit the obvious. We’re buying debt from ourselves. Period. And we’ve been doing it for quite a while. That being the case, the obvious question is: Why? If this is what we’re going to do, why do we need to go about it this way? Why would we issue currency to buy debt from ourselves in order to “spend” that same currency? That’s not “borrowing.” You can’t “borrow” from yourself. But we do. And then we close the insanity loop by paying ourselves interest in a currency we issue.

The problem isn’t so much calling out the insanity inherent in the arrangement described above. It’s self-evidently silly. Rather, the real debate centers on what happens if we recognize how silly it is and do away with it in favor of simply issuing currency with no offset whatsoever.

It’s easy enough to claim that would cause hyperinflation, or at least higher inflation, especially when you consider the distinct possibility that politicians would never relinquish the keys to the money printer. That, in essence, is the theoretical backdrop for Edwards’s “Great Melt” thesis.

“I believe that the pandemic has allowed policymakers to cross the Rubicon of fiscal rectitude to a reach a new land – one where their existing monetary profligacy can now be coupled with fiscal debauchery,” he said Thursday, noting that “at a political level, I do not believe there is any turning back now the sweet fruits of monetary-funded fiscal largesse have been plucked and tasted.”

He’s right about that. However, Albert has always been among the first to charge central banks with thinly-disguised monetary financing. What’s the difference between now and the dozen years between the GFC and the pandemic?

Well, again, one difference is simply the scope of the experiment, but from a qualitative perspective, the difference is that the general public is now more aware than they were previously of how government financing actually works in developed economies. I still maintain that the same general public is far too — how should I put this? — disinterested and distracted, to determine that already worthless pieces of paper are now even more worthless because the supply of them is growing faster than some macro aggregate. But I’d be obtuse not to acknowledge the risk that heightened public awareness undermines faith in fiat currencies enough to entrench an inflationary mindset.

In the same Thursday note, Edwards said that “any government which attempts post-GFC style austerity will be cast into the electoral wilderness.” Indeed, in the US, lawmakers on both sides of the aisle are now increasingly predisposed to donning MMT lenses. Centrists and old-guard Republicans decry MMT as though it’s an ideology. MMT doesn’t do itself any favors in that regard by holding onto the word “theory” when there’s nothing “theoretical” about it. MMT isn’t prescriptive. It’s descriptive. The same lawmakers who decry it as heresy are more than willing to accept any and all “unfunded” handouts they can extract for their constituents and districts. And no lawmaker would dare balk at unfunded expenditures to drive the PLA out of London if China ever invaded the UK. Lawmakers only pretend they don’t understand how government finance works when they don’t like what’s being financed.

So, what’s happening right now? Why are bond yields falling? Why is the reflation narrative seemingly passé despite the crossing of so many Rubicons and the breaking of so many taboos?

For Edwards, the secular inflation/reflation theme that should invariably accompany the post-pandemic policy conjuncture won’t truly play out until “later in this cycle.” Markets “have been too early in betting on the reflation trade and are now set up for a huge disappointment,” he said Thursday.

Earlier, I mentioned that markets appear suddenly concerned about peak rate of change in earnings and growth more generally. Edwards applies the same logic to deficits.

“The OECD expect all headline deficits to shrink sharply, but the US stands alone in facing an unprecedented discretionary fiscal tightening (of around 5% of GDP) despite the headline deficit staying at a high 10% of GDP,” he wrote. “That tightening begins to unfold as we progress through the rest of 2021.”

If it’s the change in the deficit and not the absolute size of it that matters when it comes to driving growth, then the US is staring down a fiscal headwind which, for Edwards, “suggests the inflation trade has a long way to unwind yet.”

Ultimately, though, Albert believes there’s no going back. As he put it, “the sweet fruits of monetary-funded fiscal largesse have been plucked and tasted.”

Of course, the rich spent the last dozen years savoring the “sweet fruits” of monetary largesse. That arrangement was lampooned and derided mercilessly for more than a decade as an exacerbating factor in the widening wealth gap.

And yet, the notion of leveraging monetary accommodation in direct service of the poor and middle-class is everywhere and always greeted with cries of “Weimar!” and “Stop the socialists!” Sometimes by the very same people who argued, post-GFC, that central bank profligacy, if it was destined to continue, should be directed to demographics that can use it.

If I didn’t know any better, I’d be inclined to think some of the same people who spent the post-GFC years penning screeds about how central banks were perpetuating inequality, were themselves benefitting handsomely from the very same dynamics and now aren’t particularly keen to see governments put their fingers on the scale in favor of Everyday Joe and Plain Jane.

It’s easy to decry inequality. And it’s not all that difficult to correctly identify its causes. Neither is it hard to champion the plight of Main Street from behind the ornate wrought iron of a gated community.

Populists in name only. Finance is full of them.

And that about sums it up – elegantly as usual. I hope your health is good H because if you don’t keep penning these I’m going to be lost. Muchas Gracias

Thank you that explains much.

+1

Hey H, avid reader here and a big fan of your writing. This one inspired me to ask for understanding.

You often bring up the fact that a currency issuer doesn’t need to “borrow” the money. Which I’d have to assume your regular readers completely understand at this point. But you rarely, if ever, touch on the other side of that thought. In my opinion, you often make it sound like there are no negatives from the fact a currency issuer doesn’t “need” to “borrow.” So I have to ask, at what point can a government spend to? I just don’t understand how you so often make it sound like a government can easily spend on anything and everything because they don’t need to “borrow” the money. If it’s as simple as you make it sound, why don’t they?

To be fair, in this specific article you did at least put one sentence in to show that there is a reason a currency issuer doesn’t issue unlimited currency, but I’d still love to gain more clarity on why we have/keep the “self-evidently silly” system.

Well, why do we persist in the self-evident fantasy that is organized religion? We don’t know what the threshold is. How can we? “Money” isn’t real. People’s faith in it is what, ultimately, gives it “value.” Obviously, the calculation is different for nations that borrow in other currencies or that are constrained in how much “hard” currency they can obtain via exports, etc. But for developed market nations that print reserve currencies (or something like reserve currencies) we don’t know what the “limit” is. Again: “Money” is a shared myth. Asking what the limit is is like asking how much more proof organized religion needs before it abandons the fairy tales that govern “believers'” everyday lives. And, I mean, on a day-to-day basis, one answer to why the US doesn’t spend money to the sky is because some lawmakers don’t want to fund certain things. It’s nice to have a cudgel, and budget myths work great in that regard. You’ll never find a lawmaker unwilling to spend on one of her/his priorities, especially if that priority is seen as winning her/him votes. Clearly, we can blow through the limit if we do something manifestly ridiculous all at once, like send everyone in the country a check for $20 million. But look how much money we’ve plowed into Afghanistan and Iraq. It’s all about perception. There’s quite obviously no limit on how much America can waste on “defense” if it’s spread out over years. If, God forbid, America had to fight a war with China and it lasted a decade and cost $50 trillion, I’d wager any associated inflation would come about more from from supply chain problems, etc. than from anyone in the US getting worried about the price tag.

“I’d call it sleight of hand, but it’s not clear who we were trying to fool.” Who we’re trying to fool is ourselves. Money has no value at all, it’s not real and it doesn’t exist. You’ve articulately illustrated that point countless times. So if that’s true, why do we accept payment and salary in the form of a made up fiat currency that doesn’t really exist and doesn’t actually hold value at all? The belief that the non-existent fiat currency actually holding value, not just domestically but internationally as well, is why any of this works at all. To use Bitcoin as an example, you believe that is also worthless and only holds value in that it can be exchanged for dollars which also don’t exist. Not very long ago nobody thought much of Bitcoin at all, it was worth less than a dollar. Now it’s over 30k? It briefly touched 60k non-existent fiat USD’s. What’s different now than when nobody wanted to touch Bitcoin years ago? Now people believe it’s a store of value and an asset worth buying. In that belief is where the value lies and the more believers that are converted over, the higher the value of that made up non-existent crypto will go.

Now we have a historical view of the rise and fall of a fiat currency in Rome and I believe that history is prescriptive for our current state. And I also believe that trying not to repeat the Roman monetary collapse is why we don’t just simply create trillions of dollars for the common man. At the point where everyone has an abundance of USD’s, is the point where no one will want them anymore. This kind of ties into psychology now, people want what they can’t have and they don’t want what they can have an abundance of. If we print trillions and hand them out to everyone who wants them, people will flock to another asset that there isn’t an abundance of like Bitcoin (which has limited supply) and then you’d see the rise of Crypto to replace dollars and crush the whole made up system. This is basically the investment thesis for crypto and precious metals, that we are all fools being played by the sleight of hand and that USD’s are completely worthless.

50 trillion to fight protracted war with China……I envision the Great Wall of DMZ down the center of Formosa…..DIDI and UBER drivers shooting at each other…..

First off, thank you for your time and energy in responding!! I do see what you’re saying when comparing money/faith as well as the defense spending part. However you do admit there is no way of knowing the “limit” and at some point (for example your $20M/person) the excess creation of “money” does create a problem. So it does sound like there is credibility in arguing that problems can be created from excess spending. From reading your opinion that simple fact rarely ever gets mentioned. Again thanks for all you do and taking the time to respond.

MMT theorists DO note a limit: inflation. Unless I have misread it, the idea is that taxes would be used to as a monetary policy lever to cool or juice the economy and, by extension, control inflation. So taxes are used as a monetary tool, not a source of revenue.

That may be a problem given the two year election cycle in the US House.

Couple of thoughts:

The GOP, as a collective, is stuck in the 19th century and is actively obstructing America, a much larger collective, from developing a workable 21st-century political economy.

If we are to succeed as a pluralistic, multi-racial/ethnic collective in the 21st century, we need to address (among other things) the velocity of money problem, and the only way to do that is through higher interest rates. Absent a complete overhaul of the tax code, monetary suppression by CBs will merely perpetuate the widening inequality in the U.S. and other developed economies. I think.